by Imogen Calhoun

illustrated by W. Stanaforth Donahue (ピリー)

(mirrors http://s2b2.livejournal.com/265795.html)

Venadan had hoped that he could at least pull the stranger’s shoulder back into alignment without waking him up, but no such luck; the stranger woke at the pressure of Venadan’s foot on his chest, so that Venadan’s first word to him was “Motherfucker,” and the stranger’s to him was a miserable yowl. The stranger didn’t pass back out at this either. He bit down on his second scream and sat up halfway, sweating, pulling his arm out of Venadan’s grip and getting his long hair in Venadan’s eyes. Venadan reared back. “You were out when I found you,” he said. “You were attacked. Do you remember?”

“Do I…?” the stranger said, and looked blearily out at the corpses littering the clearing. “Oh. I really don’t know why I thought ‘giant spiders’ was an exaggeration. The villagers were so insistent about it. How much leg do I have left?”

“Right ankle’s broken,” Venadan said. “You’ve got a hole in your neck, too– keep your hand off it!”

The stranger dropped his hand. His eyes were huge, tracking poorly, and he kept taking these deep, shuddering breaths that Venadan could only hope were panic and not a collapsed lung. “Who are you? Not that I want to sound ungrateful,” a pause for breath, “when you’ve been so friendly. Did you leave out my left leg because it isn’t there any more?”

“Your left leg is fine. I was just passing through.” He had enough water to spill some out against his handkerchief, and he pressed it into the stranger’s wound, eliciting another yell. Too much blood. “You’re a wizard, aren’t you? Can you close your own wounds?”

“I’m no good at physiology.” The stranger laughed, tipping his head back and creasing the wound, which was angry and red at the edges. “No, I– Let go of me,” and after a moment’s panting concentration he lifted two flaming fingers to the wound.

illustrated by W. Stanaforth Donahue

It was a good thing the whole situation had already shut down Venadan’s nose or he would have been sick. “There,” the stranger said, when he was done yelling again, “they told me — hah, they told me to — spend less time on–”

“Arson has its uses,” Venadan said. A messy cauterization was an invitation for infection, he’d learnt that the hard way at Digranaquierdi, but he didn’t think the stranger could take another attempt to clean it.

“Are they dead?”

Venadan started. “Who?”

“The spiders. Are they dead? How did you–?” The stranger looked him over. “You’re a mercenary,” he realized, touching Venadan’s armor, and then his earring. “You must be faster than I am. That’s the hard part, with spiders. They move like they’ve been greased. Or so I’ve found. It’s been a long couple of weeks. Thank you for saving me,” the stranger said. “I take it I am saved? I’d give thanks to a god but I don’t have one handy.”

There was a moment where Venadan took this for a poor joke, and then, raking a glance over the man’s ears and wrists, realized that there was no jewelry there, no sign of allegiance at all. He turned over one of the man’s hands. No tattoo on his wrist.

The godless stranger was still talking. Venadan was no longer listening. He was going to have to purify himself after he disinfected his hands, burn the handkerchief, wash the armor. Toss the damn earring. He couldn’t leave the man here, either, especially since in addition to being godless, the stranger also appeared to have left any kind of stopping mechanism behind him in his academy.

He disengaged himself, carefully, from the stranger, and laid him flat. “Good idea,” the stranger said. “I didn’t know mercenaries were so noted for it. I’m Arruén Chanaven Afuecoli. And you?”

They couldn’t move tonight. They needed a tent. The stranger’s pack would have one. He didn’t seem the type to travel light.

“Your name,” the stranger said. He sounded nothing worse than confused. “I’m sure you have one. At least one. I’d take a nickname.”

Venadan opened the pack, fumbling past three, four notebooks, six different colors of ink. The tent was buried under the remains of a food supply. There was a hole through it, and it would have to be patched, another piece of unnecessary labor.

The stranger tried and failed to sit up again. “Those are my things, mercenary,” he said. “In case you didn’t notice? I’ll trade you access to them for your initials. Anything. Your birthday. The town you were born in. The god you’re–” and a long, slow intake of breath as he caught on. “You’re kidding me!”

A fire, that was the start; once they had a fire, he could consider the other obstacles.

“Excuse me!” the stranger yelled, hoarse and furious. “You are not going to give me the silent treatment from here to Keisarya because I’m godless!”

But that was where the stranger was reasoning from a poor understanding of the facts. Venadan would take him from here to Aiha if he had to with his lips sewn shut. The goddess Adiena asked it. Adiena didn’t ask much, but she only asked once.

But after two sweet weeks of high clifftops and roast beef he’d come back to town to find a frightened courier and a message from General Devuera about some two-bit war in Sairenaica, and that was that. Devuera kept good records, and wouldn’t take kindly to a corps of three hundred and ninety-nine, especially if that four hundredth man was late because he’d been drying jerky. He’d left in a hurry. It was the wizard’s good luck that he’d slowed for lunch just as the wizard began to yell.

And now what? Was he supposed to — he slung his sack onto his bedroll — was he a nurse? The wizard was, even in the spirit of charity, not going to be much help. He had peppered Venadan with abuse as he’d cleared the camp and had evidently worn himself out with it. Now he was lying down, his attention fixed on the trees. Venadan glanced at him and hoped he was not bleeding again.

“I would like my pens,” Arruén said, without taking his eyes off the trees.

Venadan had put them aside when he was uniting their food stores. He tossed them to the wizard, who made no move to catch them.

“Thank you,” the wizard said, as they fell around his head. “What a helpful contribution to a man with a dislocated shoulder. I am in your debt.”

You have two hands, Venadan didn’t say. Thanks to me you no longer have a dislocated shoulder, he didn’t add, placing the bottles of ink one by one at Arruén’s side. The wizard had opened the journal and was thumbing past pages of mushrooms to find one with a grotesque cluster of circles on it.

Venadan went off to split firewood.

It all depended on how bad the ankle was. Arruén looked like he’d been put together in a hurry by someone who’d forgotten to buy enough clay. It was possible he could come apart at any minute. How long had it taken Venadan to cross the forest the first time? He hadn’t been paying attention. Things were so loose between wars. Maybe the wizard had tinder, and he went back over to the packs again, fishing aimlessly through them for something useful.

You could say this for the wizard: he’d planned to eat well. Rosemary dried, a little sack of beans, a head of garlic. Easily twenty ovoli’s worth of salt, in a well-warded tin. The bottle of olive oil was miraculously unbroken, and the size of Venadan’s forearm, raising the question of how Arruén carried the damned pack in the first place.

“They’re samples,” Arruén said. It took Venadan a moment before he realized that Arruén was referring to the folded slips of linen, each sealed with a faintly humming spark of power. “I’m a botanist.”

That made Arruén the first botanist Venadan had ever met who could turn a spider inside out.

Arruén said, rather stiffly, “The magic is not professional.”

Venadan chose not to press this one. He picked up his bow and went to hunt before the daylight died completely.

The game was good. He took down a couple of rabbits with the slingshot, and the quail he shot leapt, fell, and died without breaking the arrow in its breast. It had been nesting, which was a stroke of luck, and perhaps it was the eggs in his pocket that kept him wary when the white deer broke from cover just as he was turning back and stopped to graze.

His bow was still strung. He had an arrow to it before he remembered that the god of this forest might have any kind of a sense of humor. He lowered the bow, and took a step forward, then another. The deer didn’t bolt. It was no longer even pretending to graze.

“Well?” Venadan said under his breath. “Are you going to tell me what you want?”

The deer sidled back, then turned, apparently uninterested, towards a gap in the trees. It paused in the opening.

Well, that was an easy enough offer to turn down. “I can’t leave my companion. Thank you.” And, he added, internally, before he followed a strange god’s avatar into a strange forest, he would rather spit on a church and spill blood in a crossroads; but he let himself enjoy the image of Arruén fending for himself as Venadan was courted by, perhaps, a half-dozen beautiful green boys, before he turned away.

It was dark when he came back. Arruén had put out some of the bread. He had evidently not been able to convince himself to eat, and Venadan dressed his wounds and ignored his half-hearted attempts at sarcasm and took himself off to sleep.

“It takes a lot of energy,” Arruén said. He cupped his hands together again over the water jug. The air above them burst into flames. “And I was bored. It’s amazing how little sleep you get when your ankle is broken, mercenary. Have you ever tried it?”

Still sleep-addled, Venadan opened his mouth on the answer before he caught himself. Arruén smiled, a brief and unhappy look.

“Don’t worry,” he said. “I haven’t spent all night laying traps for you, just the one. I can make us enough water for a day or two. Do you want it?”

Venadan hesitated with his hand out for the water.

“Oh– damn me,” Arruén said, and then, inexplicably, laughed. “Fine. You can’t sully your golden tongue to speak to me. Can we at least work out a system of signs? Since I am injured and you’re not leaving me here to die?”

It was better than the heavy breathing, or the sarcasm. Venadan nodded, and Arruén passed him the water. It was still warm from its creation, and it made him long for coffee — weeks, hell, a month and a half since the last time he’d been in a town with coffee of the actual variety and not just chicory root tarted up. He inhaled the steam and braced himself for another question.

But Arruén only said, “Thank you for the civility,” and put out a hand again to take it back.

The man was extremely disconcerting.

Another of his talents appeared to be speaking without pause for breath.

The roast quail took two hours more than Venadan had spent on any field meal in his life. It was incredible. Venadan wolfed it down, which Arruén said was defeating the purpose — “these are rations, mercenary,” Arruén said, picking at his thigh, proving that he had never met a ration — and began skinning the rabbit immediately to make the evening meal.

Even Arruén ran out of topics eventually, once he’d canvassed his research, the surrounding towns, Venadan’s lack of skill with the herbs, and the love life of two of his fellow researchers, who had been running around each other for years now and had left everyone else at their wits’ end for ways to bang them together until they paid attention. The last one dried up when the pot of rabbit was still an hour from giving them their next distraction.

The rain pounded on the tent, loud as the cavalry. Venadan got an idea.

He pulled open his bag, looking through the meager supply of materials. The cadurrán box was at the very bottom, battered almost to death, and he took it out with care, unlatching the little gold hook and folding it open. It was real gold, real ebony, and real ivory inside, not that the wizard would probably believe it. Arruén looked to be having enough trouble believing in the fact that it was a cadurrán box in the first place.

“You play–?” he began, and then winced. “All right, don’t look at me like that. Are you bringing it out for a reason? Are you offering me a game?”

Venadan rolled his eyes, and held out the kings to Arruén: red or white?

Arruén took white, and settled back against the tree. “I have to warn you,” he said, his voice suddenly cheerful. “I am absolutely atrocious.”

It wasn’t a joke. The first game took half an hour, but that was only counting all the times Arruén had to ask him to mime the motion of the various pieces. He seemed particularly bad at remembering how the bull went. The second game took fifteen minutes. The third was interminable. Arruén insisted that baring the king was a coward’s way to win a game, and refused to forfeit merely because Venadan had ten pieces left on the board and Arruén only the one. Each time he moved his king he took longer about it, until Venadan at last threw a soldier at his head. Arruén claimed this as a moral victory, and Venadan, of course, could not argue about it.

The fourth game, Arruén said, “It’s obvious I will have to give you a handicap.”

Venadan lifted an eyebrow.

Arruén grinned. “I’ll ask questions,” he explained, setting up the board more or less correctly. Venadan reached over him to fix the red counselor. “Thank you. Then I will guess your answer. If I guess right, you lose a piece. If I’m wrong, I do. Now you are going to roll your eyes at me.”

Venadan rolled his eyes again, and Arruén crowed and pocketed the stray soldier.

The opening gambits began. Venadan was shaping something he’d learnt off Amidai back in the Amroque, and Arruén was, as usual, scattering soldiers like they were whole platoons. With his cavalry in place, Venadan saw an chance to take a bull. He was lifting his rider when Arruén spoke in a hurry. “Are you from Allauca?”

His mother’s house had been two miles out, in the settlements around it, but that was quibbling. He tossed Arruén the rider instead with good grace.

“Revenge,” Arruén said, satisfied. “Ha! I’m from up the road. Adlada. I recognized the accent.” He moved the bull straight into the line of Venadan’s chariot.

Venadan took it in a single, decisive motion, before there could be any more surprises, and ignored Arruén’s groan. He’d been to Adlada’s library before; there wasn’t much else in Adlada, except a few olive trees and a judge who had been sweet on his mother. He couldn’t remember much about the people.

He countered Arruén’s other bull with a soldier, and then sat back to consider the board. Arruén frowned. “I know you can read,” he says. “Don’t think I didn’t catch you looking over my shoulder. Do you care for it? No, that isn’t a fair guess.” He squinted hard at Venadan, taking his measure. “You read novels,” he said, triumphantly.

This was more impressive, and Venadan swept a hand over the board, to indicate that Arruén should take his choice. He tried not to flush as well, a task made easier by the fact that Arruén, with an air of great confidence, took a soldier that Venadan had forgotten was still in play. “I won’t insist on the point,” Arruén added, “but I could take a whole suite of them by guessing titles. I’m sure you love the Mirror for Misers. Everyone ought to. –Do you know, this is the ideal venue for a discussion of literature, since you can’t contest my claims.”

Venadan took the opportunity to threaten his king.

They went several harried, literary rounds before Arruén remembered his cheat again. Venadan was in mid-move once more. “Do you,” he said. For a moment Venadan was sure he was going to renege and ask about his thoughts on Hellagan. Then he brightened. “Are you married?”

Venadan knocked over his king in surprise, then, righting the king, knocked it over again laughing. Arruén folded his arms. “That means you forfeit, I understand– you may take a breath any time you please. I’m serious. I wish you could explain the joke.”

Venadan wiped the tears from his eyes, and gave him a look.

Arruén turned brick red and moved his rider backwards. “Well!” he said, when he’d composed himself. “Soldier’s luck.”

Was that a proposition?

“Me too,” Arruén added, tucking his hair behind his ear. “Or rather, I take what I can get. But I’m partial to men. Is that why you joined up? For the pickings?”

This was an old joke, and not worth laughing at. Venadan moved a soldier, rather pointedly.

“No, really. No one’s a soldier nowadays,” Arruén said. “After a war it’s unfashionable. You would have to have joined, oh, five years ago to….” Chagrin swept over Arruén’s face. “You were a conscript.”

Obviously. Venadan considered miming manacles, to lighten the tone, and discarded it. He pointed at Arruén.

Arruén shook his head. “I was already at school,” he said. His face was pinched. “Not a good year for me.” Venadan’s silence seemed to make him confessional, as he added, “I spent the first half under house arrest and the second half drunk. But! I did pass.”

When you came to it, Venadan thought, taking a chariot, that wasn’t a bad description of his first year in the service.

The questions became more obvious as Arruén retreated, until Venadan had admitted that he did have a sister and liked olives and drank and Arruén, faced with a denuded board, began to win. Venadan alternated moves between a repetitive threat block and the advance of one soldier towards the end of the board. It was a silly thing to do. Arruén’s king was still pinned down to the left side of the board by a couple of well-placed soldiers, but his own bull stood between the king and whatever Venadan’s moving soldier would become.

Arruén pushed forward his counselor, rubbing his neck, and said, “You could always forfeit.”

Venadan set his soldier down in the final rank, swapping it for his counselor, and pointed to Arruén. He made a sympathetic face, putting his hand on his neck: it still hurts?

“Unfortunately,” Arruén said. He smiled. “You won’t distract me that easily. I–” and then squawked like an angry chicken as Venadan removed Arruén’s bull from the board as the forfeit for his guess and mated Arruén’s king.

Behind them, the pot let out an ominous crackle.

From the look of total dismay on Arruén’s face, he’d forgotten the rabbit as completely as Venadan, who leapt up, cursing under his breath. The pot hadn’t broken, for which he was profoundly thankful, but there was only a little coating of water left in the bottom and the vegetables had burnt to the side. Venadan groaned and scooped out the remains of the rabbit, which had a texture which didn’t bode well for its taste, into their bowls, and came back to the cadurrán board, hoping that Arruén could be imposed on for some of the ruinous salt.

Arruén could be. Arruén, in fact, added so much salt to his rabbit that Venadan suspected his goal was to remove all other flavors entirely, and he took only occasional poker-faced mouthfuls even then. He made a desultory attempt to make fun of them both, but he seemed to have most of his attention on assembling some strange piece of artwork with the cadurrán board, the white pieces curving across the bottom squares where the red king stood and then leaping up to meet a red bull on the far left. The light was fading. Venadan set down his bowl for a closer look.

“It’s the Vessi,” Arruén explained. “That’s Keisarya” — the red king — “and Aiha, and the sea.” Presumably the sea was Arruén’s foot. That made the barren space in front of Arruén the Amroque. Arruén followed his gaze, and pushed a finger forward into one of the squares a little northeast. “Digranaquierdi,” he said. To his credit, he did not say it with pleasure. “I assume you were there.” He moved the king a quarter inch to the right. “Or you’ll tell me that you were there, anyway.”

Venadan knew what was coming next. He picked up a rider, looking for the mountains and Adlada, but he wasn’t in time to forestall Arruén’s lazy, curious voice. “Your goddess had a taste for drama in that one. Some member of the troops and the bloody head of Foloneu. Was that where you were dedicated to her?”

Where he was dedicated to her. It was the method of question that made him answer honestly. Arruén had obviously meant “your goddess” for a barb; it was like him to instead present a kind and easy way for Venadan to lie. Venadan put down the rider, and found a red soldier.

“No, stupid of me. Sorry,” Arruén was saying. His brow had furrowed, and he had moved his finger away from Digranaquierdi. Venadan had no intention of touching the spot. He hefted the soldier, and then touched it to his earring. He closed his fist tight around it.

There was a moment where Arruén thought he was at the outset of an interesting story, and then it connected, his eyes going very wide. “Oh no.”

It really was very close to being funny. Venadan shrugged, and put down the soldier.

“I’m an idiot,” Arruén said. “I– We thought the story wasn’t true. They are always inventing miracles. It was three years ago, I still don’t know if– We heard,” he said, trying to make it sound like an impossibility, “that you– the battle was going to be lost, and she walked through you and took the whole camp?”

Venadan nodded. He watched Arruén pretend not to be afraid to be sitting across from a man who had killed four hundred men and a general of the armies of Jallón. Arruén did it creditably. He said, “Do you remember killing him?”

The old remembered anger closed over him, but he did not know how to say it. The cadurrán board could not tell Arruén about the thirty other prisoners-of-war who had been chained to the same post as he, the ones who had not had a goddess step out of the air and offer them a door, the ones who had been found in the same welter of blood as the rest of Foloneu’s camp. He couldn’t mime the Jallonese soldiers who had died because they stood between his sword and the outcropping where he had become himself again.

Instead Venadan shook his head. He didn’t remember any of it.

“That’s good,” Arruén said. He hesitated. “I’ll clean the pot,” he said, finally, “if you bring it here.”

Venadan got up to get him the pot.

The day stayed fine for them as Arruén learned again how to walk. Venadan went ahead of him, sometimes moving larger obstacles aside. The path was too rocky to allow for any speed, but they weren’t in a great hurry, and Arruén kept up his store of anecdotes, if a little muted for the effort that it took to place his foot each time.

Around noon, they came to their first crossroads.

Venadan looked at it with deep pleasure. He’d been through here on his way to Agalil. It meant they were closer to Keisarya than he’d thought, and, glancing ahead at their way, it meant the road was going to be much better maintained, easier to drag a man along. They’d have to visit the forest’s shrine first, to make sure they made it out, but that was a half an hour’s walk along the east-west road.

He lay his sword down carefully across the path, and stepped into the roundabout. Someone had even laid pebbles around the center circle, a little fence to call Adiena down and a gate to let her in, to keep Evarda from having all her own way. He turned back to offer Arruén a hand, and saw that the wizard was looking at him with a troubling expression of pity.

“You don’t have to do that,” Arruén said. “There’s no god here.”

Venadan took an instinctive step backwards, towards the fence.

“I’m not joking. There’s no god in the crossroads.” Arruén searched for something in his face, and, not finding it, sighed. He picked up the sword and handed it to Venadan. “You’re always so skeptical, mercenary. Don’t you think I know my own business?” With that he stepped into the roundabout. He stepped over the pebble fence, careful not to let his dragging foot break the circle of stones, and stopped in the center. He waved his arms, then managed a sort of hop, stumbling at the end of it with a laugh. “Damn. Remind me to leave my dramatics to things that don’t strain me. Should I curse her? Evarda? She’s not listening. There is no god in the crossroads.”

Perhaps he had some kind of protection; but he’d said he was godless, and he was godless, dammit, there was no mistaking it, not an amulet or a piece of jewelry or even a tattoo to mark him. It couldn’t be a magic thing. He’d seen wizards hesitate for half an hour at the great junction in Aiha with their heads kept low, just because the rumor was that Evarda was paying attention that day.

Arruén sighed again and clapped his hands. A bolt of light washed over the crossroads, and for a moment everything shone, the forest in the pale blue of its god, a rusty glow for Adiena on his own hands, the pebbles the same color; even the road to Keisarya in the distance picked up a shimmer of gold. Except Arruén, who was the same. And the crossroads.

“She was real,” Arruén said as the colors ebbed. He shrugged. “She isn’t anymore.”

When they turned towards the forest shrine, Venadan hesitated a long time before separating the road from the roundabout anyway. Arruén, for once, made no comment.

The path up to the shrine was well-trod. Not swept; no priests. On his way in, he’d made a small offering, and the god had not shown up to give its opinion of the matter. He wasn’t sure what to offer this time. Arruén was no help, his eyes fixed on the grove, his progress still quiet. Meat would be poorly taken, and the spiders had done an number on most of Venadan’s incense, but at least there was some left. And forest gods could be strange about blood. Perhaps if they simply left coins–

Venadan heard a thud behind him and then a soft curse. He turned to find Arruén in a pile on the ground. Arruén’s stick was still standing a few feet behind him, tangled in roots he’d missed in his abstraction. Venadan offered an arm, and Arruén took it, heavily, using Venadan almost entirely to get himself to his feet. There was a vertiginous moment while they both waited for Arruén’s ankle to hold.

It held. Arruén smiled at him, giddy and too-close, and then, his gaze shifting to the grove behind Venadan’s head, lost it again.

They left the stick behind. Venadan helped Arruén past the two poles that marked the entry, and down the long, sloping path to the gully where the shrine stood. The creek that ran through it picked at their attention, first airy, then musical, then distractingly verbose, so that it took Venadan a long time to realize that it was speaking, that it was, in fact, saying, He is not welcome here.

Arruén’s hand stiffened on Venadan’s arm. “I bring no disrespect,” he said. “I’m sorry, I’m not– I’ll–”

“He’s no enemy,” Venadan said to the stream. They were stopped not two feet from the footbridge, and Venadan risked a cautious step forward.

The water rose, and he backed off in a hurry. He is not welcome here, it said again, and again. He is not welcome here.

Arruén pried Venadan’s fingers out of his bicep. “It’s all right,” he said, looking worriedly into Venadan’s eyes. “You go get us safe passage.”

“He can’t get back up that slope without help,” Venadan protested. The stream made no answer. “He can’t harm you from here.”

Arruén rolled his eyes and took two careful, slow steps back, till his back was resting against the trunk of a tree. “The god also can’t harm me if I don’t provoke it,” he said, his voice equally slow, explaining it for the stupid soldier. “Just go ahead. You’re nothing to the support I get from this– this laurel,” he finished, and his eyes narrowed in suspicion. “Which shouldn’t be in this wood anyway, as it’s coniferous. This is an old place.”

He is not welcome here, the stream said, and Venadan took a hurried step forward before he spoke to Arruén and blasphemed twice in one minute by speaking his mind on the subject of laurels.

Over the footbridge the sound of water was much louder, mingling with and changing the rustle of the trees, rising with the wind, till all Venadan could hear was one uninterrupted murmur that said, as he opened his pack, “Adiena’s son chooses strange companions.”

“No son of hers, just one of her armsmen,” Venandan said. He pulled out the string of cash. “We ask a safe way through the woods.”

“And what good will those do me?” the god said. It hung from the trees above the altar like a creeping vine. It had not been there a moment ago. “Better to leave me your baggage. For him I’d give you the freedom of the forest.”

Venadan discarded a number of responses before settling on, “I don’t come through here very often.” He set the incense in the bowl. “It’s a generous offer.”

“It would be good sense to take it.” The god peered down at him. “I could kill him for you, for nothing at all.”

Venadan’s hand fumbled on the tinderbox, and for a moment, he gaped up at the god, as mute as he’d been for days. He swallowed hard. “What has he done to you?”

“He is safer dead.” The god shivered, and it bent its long neck to bring its face to the bowl. “You are shepherding a wolf, Adiena’s son.”

Over his shoulder, Venadan could see Arruén through the curtain of leaves, blurry and green. He’d pulled out his journal and was scribbling something with great intensity, probably about coniferous forests. He showed no sign of having heard anything at all. Venadan sighed, and turned back, striking a light. “I’ll vouch for him,” he said, feeling ridiculous.

The god took a great deep breath and rose, growing stronger in the smoke. “Safe passage for you on the road,” it said. “Safe passage for him when he is with you.”

Venadan bowed and kept his head bent against the dirt until the wind let him up again.

Arruén snapped his book shut as Venadan approached, trying not to look as though he’d been trying to eavesdrop. He scratched behind his ear with the pen, leaving a trailing line of ink. “I take it we are not totally abandoned by all help,” he said, “judging by your sunny countenance. Might we leave before I’m drowned in the world’s smallest and ferniest flood?”

Against his will, Venadan smiled. He offered the wizard his arm for the path back to the stick. It was strange, he thought, as they made their way up the slope, how they’d both known that the stream was talking about Arruén.

They made good time in the afternoon, something of the feeling of the shrine chasing them off. Arruén seemed to be walking well. He used the stick on slopes, or to feel for roots, but otherwise was at last putting his feet properly, letting his ankle take his weight and stretch itself back into shape. The monologue hadn’t quite run out but it had slowed to a trickle of tangentially relevant gossip about people Venadan did not know. He was amused to realize he recognized some of the names from Arruén’s early narration, even worse to realize that he was fairly curious about the outcome of Yahari and Sousan’s endless, circular courtship. It was a good thing they were nearly done or he’d end up a fishwife.

They set up camp in a broad clearing with a firepit still recognizable in the center. There were ferns all around the edges. Auspicious. Venadan made sure Arruén had enough food to be going on with, and set out into them to pray.

He paced out the circle and door in the dirt, and settled himself into it cross-legged, and knew within about half a minute that he wasn’t going to have any luck.

He’d learned to pray after the war. His mother had taken him to services, of course, and he’d made offerings like everyone else in the army, but it wasn’t until the army had been disbanded and he was a free man again that he found out how little he knew about it. It had been a hard time for everyone, his brother surly, his sister impatient, him fidgeting like a child, and at last she’d dragged him away from their altar, hauled him halfway through town, and put him to work at the inn cleaning up after the drunks. And when he came home, exhausted for the first time in weeks, it had been easy to fold his knees and say something. If not thank you.

His sister had never really believed him. Then again, his sister didn’t believe in earthquakes, foreigners, or giant spiders, either.

But you needed to have a clear mind, even if you couldn’t have a calm heart, and all he could think about was the sound of the mosquitoes, coming out from cover. He opened his eyes.

“You are very good at the letter of the law,” Adiena said.

The mosquitoes had not stopped. She wasn’t even fully there, just a shadow in the shape of a woman, and Venadan met her eyes without trouble. “Difficult problems take complicated solutions.”

She lifted an eyebrow at that, but put out a hand for him to kiss, which he did, acutely aware of the fact that he still hadn’t purified or even washed the earring. “I didn’t know soldiers found it difficult to retreat.”

“When we don’t have anywhere to retreat to.”

“That is specious,” she said, severely, and he ducked his head in acknowledgement. “He is not a lost child.”

You are shepherding a wolf, Adiena’s son. “Should I leave him in the forest?”

“It would please me if he died,” she said. Her voice was distant. “You’ve earned time. I will give you three days of it. Then I will tell you what exactly he has earned from me, and you will do it.”

Gods’ faces were different, even hers, which he knew so well. But he’d seen this expression before, the first time he saw her; when he woke in the royal camp, his hands still chained behind him. He had said yes to her then. He hadn’t looked back.

“Three days,” he said. He closed his eyes.

“You’d better hurry,” she said. “I know you’re squeamish.”

It was hard to guess when she might be gone, but when at last he opened his eyes, it was on an empty copse and a scuffed symbol in the dirt. He still hadn’t prayed, he thought ruefully, and got to his feet.

He took the long way back, to pick up a rabbit on the off chance he could wheedle the wizard into more of his roast. There were deer again. He was beginning to be angry about the deer, the more so for the white one that loped across his path and stared for a long moment at his ragged face before vanishing again into the woods. There were omens, and then there was bait. Still pondering over this, he rounded a corner in the path and saw the camp.

The wizard was asleep, and two feet from him was a manticore crouched to spring.

“The god-eater belongs to me,” it said. He’d never heard a manticore speak before. It was a high voice, insistent like a child’s or a cat’s. “Come out, and I’ll be quick with you.”

illustrated by W. Stanaforth Donahue

He hesitated too long. The manticore took three steps towards the pit and found him.

Its barbs were too short for close quarters, which was the only comfort as it sunk the first row of its teeth into his shoulder. He shut his eyes on the pain and stabbed up and his knife made contact, slipping between a pair of ribs, and Arruén said something that he couldn’t hear, then louder, “Get away!”, which was sweet, and then Venadan realized he was saying, “Get away, mercenary, you idiot,” so he made the effort; he pried the jaws back, his hands slicing open, and the manticore screamed. He screamed back at it. He kicked where he’d left his knife and made it free. Just in time, too, as its hide burst into flames.

It rounded on Arruén then. Arruén was chanting something, maintaining the flames, and did not know that the manticore was still alive. The tail was rising. “A shield!” Venadan yelled. Arruén’s eyes flew open and his arms crossed, instinctively, and the fire went out and the spines glanced harmlessly off the solid air.

Arruén breathed out, as the manticore yowled in pain. “Why won’t it die?!”

Venadan managed, “The heart,” and Arruén reached into the manticore’s chest and got it.

The manticore died. Venadan, his shoulder still worryingly bleeding, sat up far enough to consider the hunk of bloody meat in Arruén’s hand, and the absolute ease with which he had reached through an animal’s skin and muscles and ribs. After a while he said, “I thought you said you were no good at physiology.”

“I thought you said there were mostly bears in these woods,” Arruén countered, dropping the heart. “Is its blood corrosive? It feels like it might be.”

“Could be,” Venadan says. “I’ve never killed a manticore.”

Arruén laughed, shocked, and came and sat next to him. “I need to bandage that shoulder.”

Venadan nodded. “And quickly. Unless you’re hiding a talent with skin.”

“More’s the pity,” Arruén muttered, and he took off his shirt, which was completely unhygenic and ridiculous, and pressed it to the wound. He glanced around helplessly for bindings, and lighted on the second half of the spare blanket, pulling great strips off it as though it were linen instead of wool. He saw Venadan’s eyes on him and smiled. “Simple trick,” he said. “You find the place where it would part, and you convince it that it doesn’t need force to do so.”

“Straightforward.”

“Most of magic is.” Arruén finished tying it, against the sudden pallor of Venadan’s vision, and sat back. He was paler himself, and he looked at Venadan with a bad attempt at cheer.

“You can fight,” Venadan said, and then could have impaled himself again. He tried to salvage it with, “For a botanist.”

“I’ve fought bears before. A manticore is a step up. Aren’t they demigods?” Arruén wrinkled his nose. “I’d have been a naturalist, but animals tend to take against me. I can just about manage to befriend a dog. Otherwise it’s catch as catch…. I….” He met Venadan’s eyes, accidentally, and the story seemed to dissipate. Most of the rest of the clearing seemed to dissipate, too, and it became briefly difficult to distinguish between blood loss and the welling-up of relief. Venadan put out a hand for him, and Arruén took it. The clearing was so quiet, Venadan could hear Arruén’s breathing, ragged at first and then big gulps of delighted air.

Of course the wizard ruined it then by saying, “Where did you learn to fight?”

Venadan let go of him, surprised and annoyed, and sat up the rest of the way.

Arruén frowned. “I don’t–”

Venadan looked pointedly at his bandage.

“Oh,” said Arruén, and then, ugly, “Oh. Was that a moment of weakness?” Venadan reached for him, but Arruén shook him off. “No, no. Thank you for clearing that up. I’d thought for a second you might have ranked me almost as a human companion, but I see that I’d extrapolated from what was really, all things considered, appallingly little information. In the future I’ll keep myself from imposing on your time!”

Venadan put his hands against the ground, in order to get to his feet, and discovered that he was not going to be able to do so for some time. Arruén didn’t appear to notice. He had already leapt up, and was pacing across the clearing to reclaim their bags. He was saying something about trust. “You don’t owe her anything,” he said, and threw his bag at Venadan’s feet like a shotput. Now he was saying something about pity. Venadan couldn’t follow it. To his relief, he realized that he was in a great deal of pain. It was easy to lie back down, and to let the weight of the day pull him into darkness. It was not quite playing fair, he thought, rather vaguely, but he was of the opinion that you took the advantage you were offered.

His instinct was to grab for the wrist holding it, but his shoulder made it impossible. When his sight returned, it came back dim, and Venadan had a wild moment in which he wondered if manticore venom could make you blind before he realized that the dimness was natural; it was before dawn, and his captor was blocking out the east, and also it was Arruén, his hair fallen loose around his face.

“I figured it out,” Arruén said. He sounded calm, for a man who had gone mad in the night. “You were perfectly communicative yesterday when you thought we might die. So you must be allowed to make exceptions for situations of extreme danger. Like having a knife held to your throat. By your traveling companion of a week’s vintage. Isn’t it ingenious?”

“…” Venadan said, and then, with more of an effort, levered himself up a little on his good arm to see what would happen. Arruén was as good as his word. The knife slipped against the skin of his neck. It wasn’t sharp enough to draw blood easily, but it only took a good lateral motion, really, and forearm strength. Which Arruén had, holding him down like he was, though most of the motion was in his thighs, one on either side of Venadan’s hips. How had he slept through this? No, he had more pressing questions. “You can’t be serious.”

Arruén half-invisibly frowned. “I’m holding you up, mercenary, be polite,” he said. “Which reminds me. What is your name?”

Venadan groaned, and flopped back against the ground. “Venadan dey Kurraisha.”

“Ha!” Arruén said, delighted. “What army?”

“Under General Devuera. Her irregulars. Under her in the war, too. Did it keep you up at night, not knowing my commanding officer?”

It was Arruén’s turn to be briefly silent. When he spoke again, he said, “I’d had this impression that you weren’t so sarcastic.”

“I was mute.”

“Yes, that’s a perfect example.”

Venadan elected to be mute again. Arruén’s ankle had to be all but healed, the way he was kneeling, and he had a brief flash of anger at the thought that just when he could have fairly left the madman in the woods to walk the rest of the way, there had to be all this blood loss. It was a thought that brought with it the realization that the blood loss had continued overnight. He was not just tired. He was faint.

“Not one for light conversation, are you,” said Arruén. “Well, I didn’t wake you for it. Have you noticed that you are bleeding to death?”

“Just now,” Venadan said. He lifted a hand to his shoulder.

“Don’t do that,” Arruén said sharply, as Venadan’s hand came away red. “I thought perhaps I would skip the conversation in which you tried to convince me that you were fine. Not that one could call it a conversation. More of an assemblage of you shaking your head.” He looked briefly repentant. “I could have waited until day.”

“I don’t think so. I might have been harder to wake tomorrow.” Venadan thought about shrugging and quickly revised the plan. “Spare me your cautery trick. We’re not so far from the forest’s edge, and then it’s a day to Keisarya. If the hospital is close enough to the gates, and there’s no quarantine–”

“–and we don’t encounter any other manticores, or bears, and I don’t weaken my ankle again, and you actually manage to communicate your worsening condition,” Arruén interrupted. “No. We’ll go back to the shrine.”

“The god didn’t want you there.”

“The gods don’t want me anywhere,” Arruén said matter-of-factly. “It won’t be any particular trouble to anger this one too.”

The light had been rising as they spoke, and the trees behind Arruén’s head had gained definition and color. Venadan could see the tension in his narrow shoulders, the awkward way he held the knife, the blue of his shirt, and finally the long planes of his unhappy face. Arruén caught him staring, and gave him a look of comical surprise.

It was suddenly the obvious thing to do, to reach out and put his hand behind Arruén’s head. It was simple to lean up, against the knife, and kiss him, at first quick and gratifying and then the beginnings of long and exploratory and then dizzyingly hard to maintain. He groaned, and the knife slid. Arruén jerked back. His face was flushed. Venadan opened his mouth to say something inane, and remembered Adiena.

“I have two days,” he said, instead. “My god gave me two days. Or I’m to kill you.”

Arruén gaped at him, and Venadan groped for something else to say. He tried, “Obviously I would prefer not to.”

“Obviously,” Arruén agreed, faintly. He sat up, taking care to keep the knife where it was. “You’re very gifted at disrupting a conversation.”

“I was born with it.”

“I imagine that you will probably die with it,” Arruén said. “Or because of it.”

“Your safe passage is only with me, anyway,” Venadan said. “We can’t go back.”

“I can see there are a number of obstacles to it, but there are also a number of obstacles to you dying,” Arruén said. “We’re not discussing this. When we get you to the shrine, we can reconsider the facts. I’m sure there’s some logical, sensible loophole at the center of all of this that we can negotiate together. As you may have noticed I am gifted at those. Were you also ordered to kiss me, in case it might turn out to be my last wish?”

Venadan resisted the deep urge to ask, Is it? “That was my own bad idea.”

“I’ll let you know when your ideas are bad, mercenary,” Arruén said. “Venadan.” He grinned, all of a sudden, wicked and small. “Since you obviously can’t tell on your own.”

Venadan clapped a hand to his forehead as the blood rushed from it. “You’re a medical emergency,” he said. “I am going to disrupt the conversation again. What did it mean yesterday?”

Arruén looked perfectly blank.

“By the– ‘God-eater’.”

Significantly less blank. “You did warn me.”

“The manticore called you a god-eater,” Venadan said, doggedly. “The forest god wants you dead. And my god has condemned you. What did you do?”

The morning was settling on them, and they didn’t have time for this, but Arruén said neither of those things. He sighed, like it was a great relief, and said, “I wasn’t always a botanist.”

Venadan, with a superhuman effort, did not comment.

“I was eighteen,” Arruén continued. “My friends were eighteen too. Navemi and Maddai. We had been studying contracts, and we’d gotten to the part where you discussed a deal with a god. None of us were ever very strong with magic, just too smart for our own good, and we decided we were going to fix that. We were drunk, obviously. We went down to the crossroads at midnight.” Venadan stiffened, and Arruén moved the knife, so as not to nick his throat when he swallowed. “This was against the rules,” he added, unnecessarily. “Which is why I wasn’t executed for what followed. We made deals. Stupid ones. Nothing that came true. I made a joke, I said, I’ll give you a hundred years of life for the loan of your power. And Evarda came.”

“Even wizards don’t–” Venadan said, and then managed to stop himself from saying the rest, but Arruén had caught his drift. He smiled, mockingly.

“I thought if it was ridiculous, she wouldn’t take it,” he said. “But there were a hundred years of life for her to take. Theirs.”

He sighed again, and got to his feet. “Then I killed her,” he added. “I have to use the necessary. I’ll answer your questions when I get back.”

But by the time he’d got back Venadan had made up his mind to say, only, “We’d better get going.”

Arruén said, “I could send you like a cannonball, but I believe the trees might get in your way,” so they walked. Venadan put his head down and pulled to it like an ox in harness. It took most of him to manage it. Arruén recognized it, and didn’t make as many jokes as he’d made on the way down. Those he made did not get any better.

They stopped for a meal two hours in. They played cadurrán. “The real rules, no blackmail imitations,” Venadan warned, so Arruén resorted to cheating wildly, moving his counselor halfway across the board while Venadan was busy trying to keep down the hardtack. He still lost, of course, but he seemed much more cheerful about it. He was in the middle of telling Venadan exactly why this was the first step in an extended campaign when Venadan blacked out halfway to his feet. It took him three tries to get up again. Arruén did not finish the thought.

The second leg was more complicated. It seemed to take a very long time, and a number of different times. The sun would slip behind a tree, and he would see Akshaha ahead of him on the road. The shadows of his platoon muddied his step. He was hallucinating, of course. He’d done it before and didn’t care for it. There wasn’t much to hear while you were hallucinating, and it took all your attention to remember that you were not going to be let off walking for injuries in the line of duty and that you still had miles to go.

He didn’t remember getting to the crossroads. He didn’t remember reaching the shrine.

“Back again,” the god said. It had craned its neck down to look at him from very far away. “So soon.”

“Please,” he said. Something was wrong. Arruén was there, and his head was in Arruén’s lap, and the river was rushing around them. That was probably it, in retrospect. “I,” he said, groping for the other two words. “I seek healing.”

Other things happened before the god answered, punctuated by long intervals of Arruén swearing about something or other. But when it did speak all it said was, “Whatever you ask, Adiena’s son.” The river crept away. “This does not change our terms.”

“He is not welcome here,” Venadan muttered, as the god drowned him in blue.

Venadan knew he had been answering a line of questioning, but could not remember what answers he had made. When he groped for it it seemed to drift away from him like the rest of his thoughts, which were suspended in a blue fog, somewhere else. His eyes were closed. He decided that he was dreaming. “I don’t understand how you could have killed her,” he said. “I knew a soldier who sold his legs to make it home alive. Something took them.”

“I know,” Arruén says. “There’s been some argument. If you’re going to sell your wife at the crossroads, you shouldn’t be surprised when she disappears on you, something like that. Or it could be that there are other gods moving in to take the sacrifices. Or….”

“Or she left something behind,” Venadan said.

“Such as all of her strength,” Arruén said. “On loan to someone who didn’t know what to do with it, and didn’t take it up well enough.”

Venadan pictured Kuere, kneeling, bargaining with an empty circle in the road. He slung an arm over his eyes to dispel it. There was an image of Arruén under his eyelids, and the image was also not saying much.

He said, “Allauca’s all for Adiena. After the war I was paraded around town like someone’s prize mare. There was this priest. I don’t remember where he was from. He came through. He told me Adiena had done her will through me and I shouldn’t wish to take it back.” He paused, for Arruén to answer.

“I know there’s a point to this story,” Arruén said, rather fondly, “but I don’t know what it is.”

“I don’t want to take it back,” Venadan said to his image. “We won the war. So I don’t know what it’s like for you.”

There was a little silence.

Finally Arruén sighed. “That’s the worst part, mercenary,” he said. “I wouldn’t either.” He laughed, without humor. “I made an offer, and I got what I wanted. Obviously I wish I had been more specific about my terms.”

He wasn’t dreaming. He sat up.

Arruén’s head was turned in his direction, but it was too dark to see his face. His voice was still soft. “You shouldn’t talk. Your god might not like it.”

Venadan rolled his eyes.

“I can’t see you. I’ll assume you’re being sarcastic.” Arruén put the pen aside, and the book next to it. He turned to Venadan. “What will you do tomorrow?”

If they marched hard, if they didn’t wait, they could reach the edge of the forest by sunset. If there were no more manticores. If there weren’t any bears. Which there wouldn’t be, if he could just keep up with Arruén. He couldn’t say this. He came over to Arruén instead and sat down again.

“Well, that’s an answer,” Arruén said. He let out a long breath, and for once, couldn’t think of anything to follow it up with. It threw him badly off balance. He swallowed and looked at Venadan.

They were never going to get to do this in daylight, Venadan realized, and was startled by how much he wanted to. He shouldered Arruén, surprising a laugh out of him, and then before the moment could tip over into comedy he leant in and kissed him.

This time, he did not have to stop. Arruén pulled him back in when he tried, one hand in his shirt and then the other on the back of his head. They kissed until they were both breathless and Venadan was almost blind with desire, blind and mute. He bit at Arruén’s lip, his ear, pressed a definite kiss to the side of his neck. Arruén gasped at that last, so Venadan readdressed the point, left a mark, and Arruén actually moaned, the first wordless thing he’d done in days; to make up for the fact that he couldn’t see it, Venadan left a few more. Suddenly Arruén laughed again, and the next thing Venadan knew he was flat on his back. He swallowed a joke just in time. Instead he was grinning, idiotically, up at the man who was undoing his belt with practiced ease. This wasn’t fair. He reached up to tug at Arruén’s laces. Arruén leaned in, probably to make it easier, except that when Arruén was within reach, it was hard to do anything but kiss him again.

The next few moments were a confusion of buttons and quick, hungry kisses at inconvenient times. Arruén dove away then, and Venadan jerked his head up, but Arruén was going for the pack. He came up with the olive oil, and Venadan thanked all the gods whose names he could remember for men with a sense of preparation. Halfway through the next kiss Arruén’s hand came down, slick and cold, and wrapped around Venadan’s cock. Venadan almost swallowed his tongue.

They were going to ruin his bedroll if they didn’t move, and he thought he cared about that, and then as quickly decided that he didn’t. As soon as he was able to think again he’d reposition– Arruén’s hand came off him, and he reached up instead, worked Arruén open one finger at a time, dragging each time a new sound out of him. “Is this–” Arruén gasped finally, and when Venadan nodded, lowered himself, bit by bit, onto Venadan. There was the inevitable moment of uncertainty. Then Arruén started to move.

There was Arruén’s pale chest, the trail of hair from his navel, the moon in his dark eyes– was Venadan fifteen again to be caught up in melodrama?– Venadan swallowed Arruén’s name. Arruén laughed again and rocked his hips. This time Venadan groaned.

A room with a covered candle before they knocked it over. A camp with a firepit. A fucking full moon, anything to give a little more light as he took hold of Arruén’s hips, pushed into him– this time the groan was in Arruén’s mouth– somewhere he could ask him what he wanted and do all of it– Arruén was closer even than he was, eyes shut tight and nothing to say– he was wrong, he came first, and lost himself so completely in it that he might have broken his vow at last and never cared.

Arruén finished, and Venadan slid out of him before either of them could stop panting for breath.

If he’d wanted to sleep, Venadan admitted to himself, he should probably have spent less time unconscious for lack of blood.

“Do you ever….” Arruén began. He shifted, and said, “I’ve been trying to remember stories about what people did after they’d been used by a god. I don’t think there are any. I don’t like it.”

Venadan rolled over. There was always the mistress of the labyrinth.

“Oh. There’s the mistress of the labyrinth,” Arruén said. “That’s not a particularly encouraging precedent. Do you know–?”

Venadan knew the story of the mistress of the labyrinth; Venadan was not a complete dunce.

“Sorry. It must have been a local story,” Arruén said, misinterpreting the silence. Well, he’d had half chances. “My father always told it so that she was a local girl. A miller from Adlada. Presumably she was the best miller in the whole province, you know how it goes. A poor family, though, and she’d been engaged to the butcher’s son to bring in enough for her family to live on. Except he was a lout or a criminal or a drunkard or something, so that she wanted to cry off, but her family wouldn’t have any of it, so she got up and walked what I suppose was about ten yards if it really was Adlada, the mill’s right next to the temple….”

And asked all the gods there for the way out, a whole parade of gods, which Arruén went through as a sort of compulsive digression. Venadan closed his eyes and listened to Arruén dance around naming anyone who might be paying attention.

It wasn’t a perfect metaphor. Adiena had made an offer: one day’s service now, a lifetime’s service in a year’s time, for the miller’s daughter and her family to be protected from any revenge. The miller’s daughter evidently had not felt this deal was quite sufficient, since she’d taken it and then spilled a little blood in the crossroads to summon Adiena’s rival and offered the same terms to Evarda for the mill to be prosperous the whole year. Evarda had taken it gladly.

And (Arruén said with a certain relish) after a year’s time, both goddesses turned up at her door in their human guises, and the miller’s daughter opened her eyes very wide and said that she had no idea there was a dispute over her services, but she would be happy to give herself to whichever goddess had the best claim on her mill. Whereupon she led the gods to it, and showed them what she’d built in it: a labyrinth.

It’d been a long time since Venadan had heard anyone use words like “whereupon” when sharing a pillow.

“Whether or not it was still any use as a mill with a labyrinth in it didn’t make it into the story,” Arruén said. “The path didn’t fork, so the goddess of the crossroads couldn’t touch it. It took you back to where you began, so your goddess couldn’t say it was a portal. The miller stood in the center and watched as the goddesses realized they’d been tricked. That was always a bit more than I could believe. Why wouldn’t you run? Anyway, the goddesses agreed that there was only one person with a claim on the mill, and that was its builder, and she was welcome to it, but of course since she’d made something entirely new, she was going to have to take care of it– and when the miller went to the door she realized she couldn’t leave. She was the mistress of the labyrinth.”

Venadan thought about this. Not with any great attention. He was beginning to be comfortable at last, and with it came a realization that Arruén was breathing harder than the story warranted, aware of how they lay next to each other.

“You don’t have any outstanding offers for your family’s mill, do you?” Arruén said. “I’m only wondering.”

Venadan’s hand slid down Arruén’s side.

The conversation turned course.

Venadan took a perverse comfort in the fact that their parting would be silent and brief. It offered many fewer opportunities for insult. What would he ask Arruén for, anyway– a visit to his sister’s house, and to not mind it when everyone in the house averted their eyes from him and cleaned the floor on which he trod with ostentatious disgust? Letters which his sister would open, and which Venadan couldn’t return? To find himself a forgiving god? So it was better that they’d leave with a handshake, or maybe a more personal farewell, to put a cap on this absurd journey. There was nothing to solve. His discomfort profited no one.

He’d said a lot of goodbyes to people who had saved his life, and never worried it before, he thought, and stopped, in the road, to think this over. Arruén stopped too, and closed his mouth on a story about a coffeehouse. “Something wrong?”

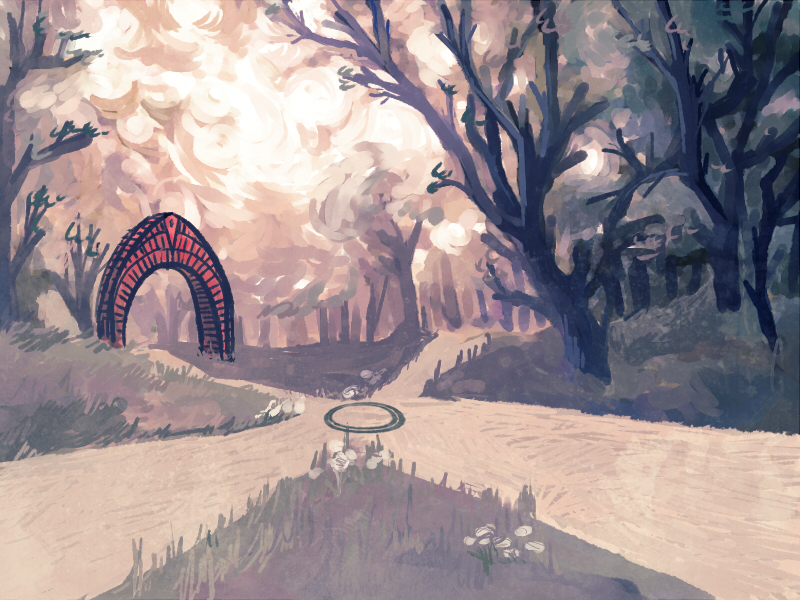

Yes, Venadan thought, and then, yes, as the clamorous voice of his instincts finally made itself clear for what it was. He set down the packs, and began to run up the road. They were very close. Five minutes, at a jog, and he was out in the crossroads at the edge of the forest, staring at the large red gate that barred the road to Keisarya.

illustrated by W. Stanaforth Donahue

He was still standing there when Arruén caught him up. They surveyed it in silence for a little while, as the sun dipped lower in the distance. Finally Arruén said, flatly, “She rigged it.”

“No,” Venadan said. “She played fair. She told me what she was doing.”

“And– how, exactly–”

“She gave me three days of time before she would tell me what she wanted me to do, and then I would do it,” Venadan said. “Then. Not if. She was clear.”

Arruén opened his mouth, and then closed it again, still silent.

Venadan took a step towards the gate. A way out, if he was squeamish. He wondered if it was for Arruén, or for him. “It wasn’t an accident,” he said. “The spiders. All the animals who didn’t like you. It was their gods. The gods want Evarda’s power back.”

“The manticore,” Arruén said. His face had gone very pale.

“Any demigod,” Venadan said. “Any avatar. Anyone with a god’s hand on them. You’re the expert. If they kill you, where does the power go?”

Arruén tilted his head back, gauging the sunlight. “To their god,” he said. There was a relief in his voice that Venadan did not like to hear. “Of course. To your god, in about ten minutes. How are we going to get out of it?”

Venadan shook his head. There was something he was still missing, some piece of what Adiena wanted that didn’t match up with what she had made. He needed time, uninterrupted time, to think, and one way or another he was not going to get it. Even now Arruén was saying, with real bitterness, “I suppose renouncing her hasn’t even crossed your mind.”

“No,” Venadan said. He closed his eyes. They’d said something, one of the two of them, hadn’t they–

“She made you a murderer.”

“No.”

“You killed four hundred men.”

“I know,” Venadan said. “I’m a soldier. She gave me a choice.”

“Oh, and you knew what it would do?”

“No,” Venadan said, for the third time, low and furious, “but neither did you,” and the spark of memory flared.

Arruén was saying something. Venadan had hurt him, badly, and if he had had time to apologize, he would have done so. The anger had already left him again. He opened his eyes. “Arruén,” he said. “Arruén!”

“What!”

“What you said to me in the shrine,” Venadan said. No. He had to be clear. “When you told me you’d make a better bargain. Did you mean what you said?”

There was a vast silence. The sun had already fallen behind the trees, and the shadows were blanketing the crossroads, washing the color out of everything but the gate, which stayed the same red. They did not have this time to spare.

“Yes,” Arruén said, finally. He wiped his hand over his eyes. “Damn you, I meant it.”

“So would I,” Venadan said. He drew his sword.

Arruén’s face, when he saw it, was worse than the fight was going to be. He did not waste time with protestations; he stepped into the green circle in the middle of the crossroads. “I am not going to bare my throat for you.”

“Good,” Venadan said, and swung for his head.

Arruén had wrapped himself in shadows before the blow was halfway down. They slid around the sword until it was like cutting through molasses, and then Arruén’s hands closed around the blade. With a wrench, Venadan turned it till it cut — blood in the crossroads — and yanked it back, sidestepping to avoid the hands that the leafmold was forming around his feet. He planted himself and feinted to the right, then made for Arruén’s back. The sword connected, the shadows a little slower to move, and Arruén howled and seemed to reach for the air and draw back a handful of fire. Venadan brought the sword down on it as hard as he could.

The explosion was tremendous. It knocked Venadan halfway across the clearing, and it left his sword in white-hot pieces next to Arruén. Arruén was staring at them. In another moment he’d put it together, and Venadan didn’t have time for that; he launched himself bodily at Arruén and wrapped both hands around his throat. Arruén was staring at him, Arruén was frightened, Arruén was furious, Arruén wanted to live, and Arruén reached through Venadan’s throat and left a hole in it when he drew back. Blood in the crossroads. Venadan fell, unsupported, to his knees, and then to his side, where it pooled over the last of the shadows as the sun finally set.

There were two women in the clearing. Adiena said, “That was well done.”

“That was the sweetest thing anyone’s done for me in decades,” said Evarda. She was a suggestion of a white dress, kneeling where Arruén had come to kneel, desperate, when Venadan had died. Hello, Venadan wanted to say to Arruén’s shadow under her, except that he was still missing most of what he would say it with. “He’s got a knack for the third option. I wonder if he’ll worship me.”

Arruén was making a demand. Adiena’s attention was on him. “Your new self doesn’t understand,” she said, to Evarda. “You had better explain.”

Evarda sighed. “I hate explanations,” she said. Something changed about her, and there were two of her, and one was Arruén, still kneeling at Venadan’s side. The other was behind him. “Foolish boy. Did you think if you asked for my power you wouldn’t get it?”

“I thought if I killed you you’d stay dead,” Arruén spat. “Venadan, you idiot, you knew I could fight– why didn’t you wait–”

“Because if he had waited until sundown he would have fought with my power on him,” Adiena said. “And he would have won. You would have died, and I would have had the power of the crossroads, and the gods would have had their justice.”

“Instead,” Evarda said, lovingly, “they have you.”

Arruén’s head jerked up. He had to swallow before he could say anything, and when he managed it, it was low, mocking, at odds with the blank expression on his face. “There is no god in the crossroads.”

Adiena looked down at him. “There is now.”

“I’m going to kill him,” Arruén said. “Except I seem to have been saved the trouble.”

“About that,” Evarda said. “Since I don’t think we can really say I’m loaning you my power any longer, I seem to have a hundred years on hand that I can’t say I have title to, either.” She knelt down in Arruén’s place again, and put her clean hand on Venadan’s throat. “And,” she added, “I like him.”

There was a great pressure under her hand, a tightness, and then his chest was being kicked by an overenthusiastic horse, and he sat up, gasping, in a clearing in the twilight, Arruén bent over him, chanting something that was knitting the last patch of skin shut. Arruén noticed he was alive before he did himself, and brought the point home by yelling, “You made me a god!”

“You asked for a sensible loophole,” Venadan said. He brushed Arruén’s face with his fingers, and coughed up a small amount of blood, but by and large he felt fantastic, much better, certainly, than when he’d been run over by a manticore last.

“I asked you for a sensible loophole two days ago,” Arruén protested. “First, I’m appalled you remember, and second, we need to have a long, extensive, two-sided conversation about your definition of the word sensible. Are you–” He stopped, tilting his cheek into Venadan’s hand, and asked, in an entirely different tone, “What are you doing?”

Gods’ faces were different. Arruén’s had not changed, exactly. Everything was in the same place; his eyes were still dark, his nose was still long, and his smile was still surprised, and wry, and a little crooked. All of it looked as though it had been shrugged on as the most convenient alternative. Venadan was almost surprised when it didn’t shift under his fingers, only slid, glass-like, away from any attempt to leave a mark.

It wasn’t quite true that his smile was the same. Evarda had looked hungrier than Arruén, but not anymore.

Arruén closed his eyes, and with a visible effort, the clearing jolted into some other shape and his skin dimpled against Venadan’s fingers, human and real again, not to mention disgusting with dirt. “I don’t think I have to do it all the time,” he said, conversationally. “What made you think I wanted to do it at all?”

“It was that or kill you,” Venadan said, bluntly. “Should I be sorry?”

It took a long time for Arruén to shake his head no, but at last he did, one quick jerk. He sighed, and put his own hand up over Venadan’s. It was freezing, and Venadan, being the silent type now, apparently, did not protest.

“I can be myself for a while,” Arruén said. He laughed. It had real humor in it, and the beginnings of excitement. “I– hmm. I could be any of myself for a while. Do you want to travel with Evarda’s old body? When she had one? Or a crow? You might have to try all three. I don’t think I can be one thing as far as you’re going….” He looked a little stymied. “Where are you going?”

“Sairenaica,” Venadan said. He lifted his eyebrows at Arruén. “My god didn’t share?”

“Your god is abominable, and you have a terrible sense of humor,” Arruén informed him. “In the morning we can see if there’s an easier way to get around.”

“Oh, can we?” Venadan said. He was grinning again.

Arruén snorted. “Yes, we can. Don’t pretend that you have objections. You made me a god. I think I’m permitted to make the decisions for both of us for some time.”

Venadan could just make out the quirk of his smile, and not much else. He said, “All right, god of the crossroads. Could we have some light?”

Arruén paused. With a growing surety in his voice, he said, “What will you trade me?”

Venadan reached up to kiss him, languorous and thorough. Arruén’s cold hand closed on his. They made a slow time of it, as behind Arruén’s head a white light began to fill the clearing, lapping at the road and coloring in Arruén’s eyes a peculiar grey.

Over Arruén’s shoulder, Venadan saw the flicker of a deer at the edge of the woods; then the forest god stamped a petulant hoof, and vanished into the underbrush.

It took him three hours to explain adequately, in detail, that he wasn’t laughing at Arruén. Venadan didn’t mind.

—

send the author a comment directly (you must be logged in)