by Tsukizubon Saruko (月図凡然る子)

illustrated by by Sakana Sara (魚 サラ)

(mirrors http://s2b2.livejournal.com/96796.html)

They found Lily’s body on September 8th, late in the morning. It was a Monday, and Mrs. Packard had to open the copy shop where she worked, much earlier than Lily was supposed to go to school; but she got a phone call at her job around 9:30 from the school receptionist, asking why Lily hadn’t either come to her first two classes or called in sick. She went home right away, and in the end broke open the door to Lily’s bedroom, and found Lily lying on her bed, watching the ceiling with a rapt, fascinated, almost peaceful expression. Her wrists had been carefully cut in two long lower-case t’s, and the short, sharp vegetable knife that had done it rested just at the edge of the grip of her fingers, as though she were deep in thought and about to tap it like a pencil to focus her mind. The blood had dried around her hands in two small puddles on the pink bedspread, like punctuation; a colon, maybe, opening a list of her mother’s screams. They eventually brought a neighbor running over to find her, to pull her away, to make the phone calls and arrangements when she couldn’t be calmed down, couldn’t be coaxed or embraced into sense. There was a special announcement at James High, and most of the senior classes were allowed to go home after second lunch.

Allison didn’t go home. She meant to at first, but then she drove around town in aimless, spreading circles, running at least two red lights, dried salt all over her cheeks. When she passed the library, where she and Lily had been going to meet to share headphones and watch a movie for History, she braked the car to a shuddering halt and fumbled off her seatbelt, flung open the car door, and leaned out of it and threw up.

She fell back inside when she was finished, and leaned back on the driver’s seat, her head leaning on the headrest and eyes closed, oblivious to the open door and the running engine and the way any traffic would have to weave around her at the curb. Trapped behind her eyes with the memory of the lipstick Lily had worn, in the shadows of her car, the last night Allison had seen her alive.

That red lipstick.

—

The county coroner called it a suicide on the 11th; there was no note, but nothing to suggest otherwise, either. Mrs. Packard was a pale and silent ghost on the living room sofa by Sunday, her bleached lifelessness drowned out by the colors of the floral pattern, surrounded by a flutter of her sisters and a mountain range of well-meaning casseroles. Even so, Allison spoke with and then hugged Lily’s Aunt Margaret with low-pitched, firm certainty, and hitched up her black skirt to lead the way up the stairs to Lily’s bedroom.

“What are you looking for?” Jenna asked, keeping her voice soft. She hated the idea of being in here, of speaking here: where the light blues and cheerful posters seemed like blush on a dead cheek, where the teddy bears piled on the shelf above Lily’s bed were a parliament of cold black eyes like birds’. She didn’t want to look at the bed — long since stripped and re-dressed, slyly and mockingly ordinary — but her eyes kept sliding back, like the whole room was a sheet of angled glass and it at the bottom. Allison was already down on her knees on the carpet, peering into the bottom rank of a low bookshelf. Her skirt was in something soft and clingy, and it puddled around her ankles, the heels of her chunky black shoes pointing up uselessly behind her.

“I don’t know,” Allison said, without turning. “I’ll tell you if I find it.” Jenna bit her lip, and nodded even though Allison couldn’t see.

Allison and Lily had been friends forever, as far back as kindergarten and preschool; they were sunny and pigtailed in their mothers’ time-washed photo albums, always holding hands. Jenna was a later addition. Her father’s job had moved the Santos family from Sacramento to Omaha when she was nine, but she had only met Allison at eleven, when they had left their apartment in the city out to a little ranch-style house in James. She hadn’t fit in well to start, but Allison had always been sweet to her: a big-eyed gawky white girl with straight As and braces, whose questions were endless but never mean. The distance between them had closed down to nothing with alarming speed, even at that age, when most girls were just bags of poison stuffed into their clothes.

Lily, on the other hand, had been nice but always distant, their three always more awkward and unsteady than either pair. For Jenna, Lily had always mostly just come with the territory. And until this year, Jenna had never minded. The year when Lily had exceeded distance into the extraplanar; the year of the phone calls and the disappearances and Lily’s strange, fragile smile.

In a way Jenna supposed they had almost been expecting this. In a way that was worse.

Allison had moved on from the bookshelf by now, and now was feeling around behind it. Finally she pulled at it for a few moments, until Jenna nearly said something in her alarm, before giving up and straightening back up on her feet, looking around. She scuffed across a windowsill, examined the dresser mirror and the space behind it as well. Her expression was far-off, vanishing to a remote point, the side of her face porcelain-pale. Her long brown hair had been pulled back into a twist behind her head, no less severe for its prettiness, and it made her look somehow naked.

“Do you — ” Jenna started to say, but before she could finish Allison suddenly turned, crossed to the closet door, and opened it — and then all of Jenna’s air was shocked out of her lungs in a long, high-pitched hiss.

The inside of the closet was a stunning wreck: clothes torn off hangers and heaped on the floor, hangers themselves bent and twisted into weird new shapes, cardboard shoeboxes of little miscellanies upended of their contents and lying in shredded fragments. A heap of photographs lay scattered, an earthquake of flat faces. That was bad enough — it might have seemed normal for a teenaged girl to anyone who didn’t know her, but against the spooky unlived-in neatness of the rest of Lily’s room, of Lily’s life, it was like a slap — but it wasn’t what robbed Jenna of her breath.

That was the full-length mirror hung from the inside of the closet door, and the huge, jagged red letters scrawled across its surface:

ALLIE

ALL THE WAY

And under the last part, a red, looping arrow, pointing from nowhere at nothing.

For a second Jenna’s fumbling brain tried to tell her it was blood it was written in, but of course it wasn’t. The letters were all neat, undripped, too dry and opaque on the glass. After a few numb seconds, though, she could finally place the substance — the tiny cracks it made in the words. Lipstick.

Allison didn’t move, didn’t make a sound. All Jenna could see was her back.

“God,” Jenna said, finally. It came out in a small fragmenting whimper, and she tried to firm her voice. “They… the sheriff was through here, wasn’t he? Didn’t anybody find this?”

“I don’t know,” Allison said. She sounded perfectly reasonable and calm, but Jenna still couldn’t see her face: her red-lettered name even blocked it in the mirror. “Maybe they didn’t look in here.”

And she didn’t say the shuddery, vile thing that occurred to Jenna next, neither of them did: that maybe they had. That maybe it hadn’t been there when the investigation had made its solemn, silent tromp through Lily’s sanctuary. That maybe it had come later. It was impossible, but that made it no less powerful or instinctive a thought.

Jenna struggled to find more words, to get them past the sticking knot of her throat. They made it out small, but they made it. “What does it mean? Do you know?”

Instead of answering, Allison reached out. Slow and calm; her hand didn’t even shake. She pushed the door further open, by its edge, until the point where its hinges stopped it. All the way open, Jenna realized you might say. She couldn’t even think why she hadn’t thought of that.

And now in the mirror’s reflection, the point of the red arrow rested directly on a framed picture, hanging over Lily’s bed.

Jenna turned before Allison did, swallowing against the dryness of her mouth. Nothing was wrong that she could even have talked about, that she could have given words to, but all of this was wrong. She felt sick, a terrified intruder, as if she’d opened Lily’s coffin at the wake and climbed inside next to her. Like feeling her own breath off a dead girl’s cool skin.

The picture was an old photograph, black and white, in a pretty silver frame. It was, she saw with no real surprise, of a scalloped mirror, hung on an otherwise blank wall. The photographer had somehow stood in a position such that he or she hadn’t caught his or her own reflection in it, or the camera’s; instead, it showed a double bed against the wall opposite, bare with its comforter tumbled half-off, the wall above unrecognizably stained and only the edge of a window just visible to the side. The mirror itself was off-center in the picture, leaving most of its interior space blank. It was a bizarre shot, now that Jenna really looked at it: inexplicable and more than a little creepy. She wondered why she hadn’t noticed it before. How long had Lily had that? She couldn’t remember having seen it, but if she just hadn’t noticed today then she might have not noticed on a dozen previous days. And they’d all been in Lily’s room so little this past year.

Allison went over to it then, startling her out of her thoughts. The glimpse of her face Jenna caught as she passed was much less expressionless, which was comforting in a way: she looked upset, but determined, like she was afraid of flying but forcing herself on a plane. She leaned over Allison’s bed, examined the picture very closely for a moment, and then lifted the frame off the wall and into her arms, turning it over to look at the back.

Where there was a thin, small book, strapped to the backing with clear packing tape. All its visible cover was a collage of vintage advertisements and postcards, stylized ’20s European women with superior smirks and cloche hats and cocktails. Printed across the top in embossed gold, it said, DIARY.

It was almost an anticlimax — except that the metal fastenings around its edge looked sturdy, and instead of the ordinary little play diary-lock, they were closed by a heavy, no-nonsense U-Haul padlock. And it fell into place, what Allison had shown her, from that last night —

“Help me,” Allison said, and now her voice was still strong but beginning to shake. And once she’d said it, there was really nothing else Jenna could have done.

—

“I need to give you something,” Lily says, and Allison slows down automatically to glance over at her. She can’t see past the reach of her own headlights, and Lily is a green-tinged ghost in the faint glow from the dashboard. Out here it gets so dark late at night, even though Omaha burns the edge of the sky orange in the flat distance.

“What?” she asks, not knowing what to expect — not knowing what to expect from anything after tonight, her eyes hurt and she feels half-awake but cabled with nerves. Lily could slap her or kiss her or warn her away, any of them could be the answer, and she wouldn’t exactly be surprised. She can’t shake the feeling that she’s in the car with a stranger. Or two strangers, maybe, and one of them has the wheel.

But Lily doesn’t answer. She leans across the front seat, inches from Allison; their hair brushes together, and her breasts press soft to Allison’s arm. Her breath is quick and light and ticklish as grass on bare feet. She smells faintly of perfume and smoke. Lily has turned on the radio, at some point on the drive home, to the oldies station, and the tinny sounds of Roy Orbison’s voice and band pour out like dry ice smoke into the car, a cheap special effect. Allison feels fingers on her neck, feather-light, doing something, and before she can flinch away or turn Lily’s pulled back, at least a little ways. She’s smiling, but she looks sad. Her lipstick makes her teeth look so white, her skin look so white. Even her hair, only blonde in the light, looks white now. Like a ghost.

There’s a plain, tiny key hanging from a thin silver chain around Allison’s neck.

Allison coasts the car to a stop, idling at the edge of the empty late-night suburban road, and picks it up in her fingers. “What is it?” she asks, and suddenly isn’t really sure she wants to.

“A present.” Lily hesitates, and now her eyes are turned down and opaque. “To say I’m sorry.”

“You don’t — ” Allison begins, but Lily won’t let her finish; she raises her eyes again and they run Allison out of words. She’s still smiling, but she looks so sad. And scared.

“I’m so tired, Allie.” She shuts her eyes, and Allison can see it, written all over her. The dark shadow on her eyelids looks like dark circles, makes them look bruised. She looks much older than eighteen, much older than thirty. She looks like an old movie star, nowhere anymore but on a screen in black and white. The radio croons, Too real is this feeling of make-believe, too real when I feel what my heart can’t conceal… “I’m so tired tonight. Can you take me home?”

And Allison does, her headlights cutting their path down the back roads of a newborn Saturday. Lily waves to her, on the walk up her backyard, a few scatters of leaves crunching under her high heels in the car’s fan of light; and that Monday morning she’s cold on her bed, all her life poured out of her hands.

—

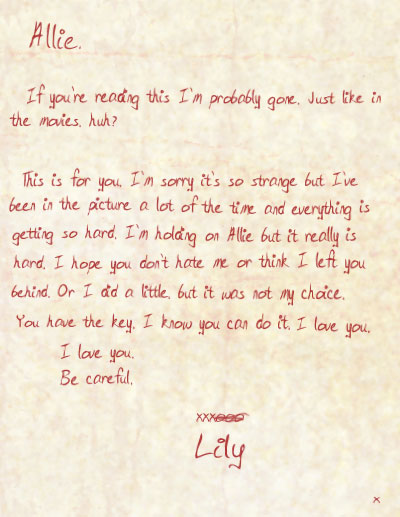

(from Lily Packard’s journal, near the front)

—

It was about a week later when Jenna’s dad gave her the gun.

She had come down to his workshop in the basement to sit with him, like she had off-and-on in the evenings since she was little, when his workshop had been in the garage instead in their house in California. She had liked it better there, honestly; it had been oil-smelling but open, orange light from the streetlights outside filtering in the high windows. The basement in their house in James was unfinished and huge, and out beyond the bare-bulb spotlights over the washer and dryer and Dad’s workbench, darkness claimed the stained concrete and the cobwebby architecture of derelict furniture. Sitting on the bench beside Dad was like perching on a piece of driftwood, floating together on deep water.

He’d been working with a broken chair that night, fixing on a new leg he’d already turned to match the rest; his safety goggles hung retired over the hook at the end of his work table. Paul Santos was a chemical engineer for DeShaw Heartland Foods, a slim unassuming man in glasses and cuffed-up oxford shirts, but he was better with his hands than you would ever guess looking at him. When Jenna had been little he had been a doctor of china dolls, a veterinarian to the fragile legs of toy horses, but mostly he had always been a woodworker in his spare hours home at night. And tonight, when he’d tightened the bolt, he glanced over at her, through the upper part of his bifocals.

“I want to give you something,” he said — his hands still on the chair, bracing things in place. “I wasn’t sure if I should at first, but I think it’s the right time now.” He nodded toward the back of his work table, well out of the line of fire. There was an old Adidas shoebox there, dusty as everything else but surely a new addition. “In there.”

She looked at him a second longer, uncertainly, but he’d already turned back to his work, so she climbed up on her elbows to lean across the table and retrieve the box. It was weirdly heavy, and she was already frowning before she got the lid off and saw inside.

The gun wasn’t big, but it meant business. It gleamed in the light like a predator’s eyes, like snakeskin, cushioned on a couple old t-shirts like a nest. It was a revolver, she was vaguely aware, a round barrel buried at the end of its long silver snout. She knew almost nothing about guns, and would have always imagined her dad the same. Jenna glanced up at him, frowning and almost horrified, but he still wasn’t looking at her.

“I have rounds upstairs,” he said, as though making conversation with the chair. “I just don’t like storing them together. But when you go out from now on, I want you to take both of them with you. And, for God’s sake, not use them unless you absolutely have to.”

“Dad, I’ve never shot a gun in my life,” Jenna finally managed to make come out of her mouth. Saying it seemed to break her paralysis, and she fumbled the shoebox with exquisite carefulness back onto the worktable, pushing it out of reach. She didn’t even want to touch the box. Her dad finally looked at her again, mildly, and then blew wood shavings off the fresh wounds in his work.

“I can teach you.” He examined the bolt with a critical eye for a moment longer, then sighed and set down his wrench, turning to face her. They were both straddling the workbench, a leg on either side, and his hands rested laced on the wood between them. They were dusty from the wood. “I’m not a big fan of guns myself, but I want you to have something to protect yourself. As much as you possibly can, actually.” And he hesitated, and then finally: “Especially after what’s happened to Lily.”

Jenna stared at him. Her throat felt very dry. “Dad… she — ”

He shook his head, silencing her, his eyes dark and serious. “No, I know. But I think you know as well as I do that that’s not all there was to it. Lily was…” He paused again, and looked away, pushing up his glasses as he thought over the rest. “From what I’ve heard, she was mixed up in a lot of things. Things that weren’t her fault, I think; but she paid for them all the same, and she won’t be the only one.”

“What do you mean?” Jenna asked. He shook his head, slowly, thinking again.

“I’ve seen a lot of ugly things,” Dad said at last, when it seemed he’d collected his thoughts all the way. “I’ve seen people be very ugly, in my life. But something about this place, right where we are…” He shook his head again, and finally looked up to offer Jenna a small, rueful smile. “You know your grandmother won’t even come visit us here, right?” Jenna frowned, but nodded; as far as she knew, after thirty years in Sacramento, Lola could imagine Nebraska only as an ocean of corn and refused to set foot in its hopeless provinciality. They always flew out to her for Christmas and Easter, Mom teasing him about “Her Majesty” the whole way. “She did once right after you were born, and then she never would again. I’ve never seen her so frightened, and she’s not easy to scare. When I was growing up every other story out of her mouth about when she’d been a girl in Pampanga was a ghost story, happened to her or her sister or another little girl she knew…” Dad laughed a little, under his breath. “But honestly I can’t blame her, either. I know I wish we’d never come here, now more than ever, and that’s the truth. I’d see if I could get us back to California right now, one way or another, if it seemed worth it; but with you going off to college soon enough, well…” He rubbed one finger under the nose-pad of his glasses, then raised his eyes back to her. They were steady enough.

“So I don’t know, sweetheart,” he said. “I don’t know what I think, or what it is about James. But it seems to me like… things get bad around here in a big hurry. And I’m not sure we’ve seen the end of it, or just the beginning. I just want you to be careful from now on, as careful as you can be. Don’t go out with people you don’t know, not even friends of friends. And never go out alone.” And he paused, and nodded to the gun. “And from now on, take that with you.”

The edges of it around the rubber handgrip, when she finally dared pick it up, were cold in her hand: like a warning.

—

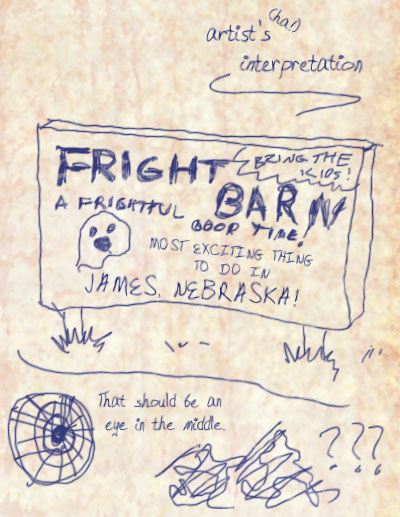

(from Lily Packard’s journal, near the center)

—

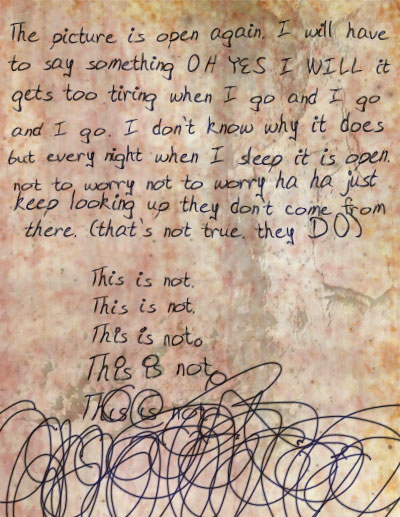

Allison read the journal, cover-to-cover, from beginning to end: everything there was of it to read. Then she read it again. She read it four, then five times, and then she couldn’t look at it anymore; it scared the shit out of her and she didn’t even want to be aware of its reality, its existence. She hid it between her mattress and her bedframe, as deep as she could. She couldn’t stand the thought of being asked questions about it.

The weeks, and then months reeled by in a shocked, slapped hush, and not much of anything else happened. Not, anyway, until the night before Halloween; the night of the Fright Barn, when everything happened. When everything came undone.

—

(from Lily Packard’s journal, just past halfway through)

—

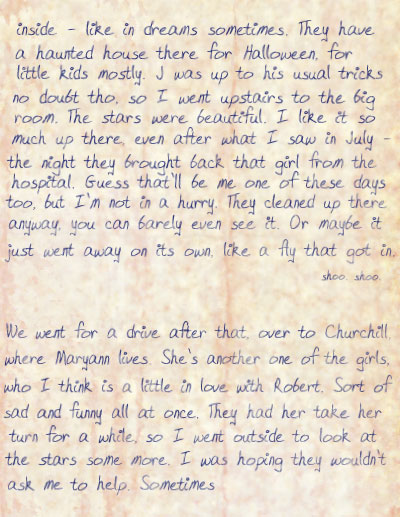

The Fright Barn sat outside the limits of James, a yearly institution most everyone at least knew about. Its billboard out on 275 had gone yellow-grey with age, sporting a CLOSED SEE YOU NEXT YEAR banner stuck to it for eleven months out of every twelve, but never without its little thrill when the qualifier finally disappeared: autumn is here, really here now, and it’s harvest time, it’s Halloween time. Half of its proceeds went to the Baptist church out by the highway, although thankfully they kept it standard — none of that stuff with the Abortion Room or Drug Addict Terror or whatever and a place at the end where you could cry to a preacher about how bad you were going to hell. Just a remodeled warren of teenaged ghosts and witches with a scratchy old tape of chains and screams playing over and over. Jenna’d only been once or twice, back in junior high, and it had been comfortably dull.

In the off-season, though, she’d heard that it got a little less boring there. There were rumors around town sometimes, especially lately, that in the winter and early spring the Fright Barn was a sex place and a drug place, providing James’s unnamed evildoers at least a windbreak against the cold. All kinds of crazy other stuff, too: that people had actually OD’d and died there, that a boyfriend had killed a girlfriend and shoved her body under the floorboards, even that the farms all around where the barn was had had cattle mutilations and crop circles in the time since all this had been going on. Jenna didn’t think any of it was true, really; half the time she even suspected the Baptists of starting the rumors to make the place seem scarier, and get more trade. Her dad wasn’t wrong: there were weird things about James, weird even to a bunch of imports like their family. But she still couldn’t picture its seamier underbelly having needs exotic enough to make it truck out into the farmlands in the dead of winter. There were drugs, and sex, and death, sure, but most of them probably happened right in the most suburban of houses, under concerned parents’ noses.

But Lily’s journal mentioned the Barn; Allison had showed it to her, and Jenna had read down the page, as much as she hated even looking at that thing. The more bits of it Allison showed her the more she hated it. It made her feel sick and almost violated more than scared, ashamed and poisoned with knowledge, like seeing a porno magazine with pictures of little kids or a used condom on the ground with a crust of dried blood. She read it, when she did, for Allison, and that was all. Because Allison needed help.

And Jenna played surprised delight over the phone when Allison said they should go to the Fright Barn, saying how much nostalgic fun that should be, even though she could hear perfectly well the grim note in Allison’s voice that said it wouldn’t be fun at all, it wasn’t supposed to be fun, it was a mission and it was one step closer to the truth Allison felt certain she needed to uncover. Diary in hand, Allison was trying to wedge together the pieces of Lily Packard’s last days on earth into a picture that made some sort of sense to her, and if the Fright Barn was one of the pieces, she had to go pick it up, that was all. And if she had to, Jenna had to. Allison would never have said that, of course, or even meant it; it was just the way things were. But Jenna pretended anyway, even if neither of them really believed it. Somebody had to hold them together. Sometimes she felt a little like they were a pair of parents, and Lily their child who had died.

So the night before Halloween, Jenna ran waving out of the house to Allison’s car, huddled in a jean jacket, a couple of sparkly little-girl barettes pinning back waves of her dark hair. And shoved under the back of the jacket, down into the back of her skirt and leggings, the revolver sat in its deadly silence, because her dad wasn’t wrong.

They drove out of town, Allison pale and quiet at the wheel but at least a little more animated than she had been, a little more able to smile. It had been hard to talk to her this past month, although Jenna guessed she couldn’t blame her. When they pulled up into the dark, roped-off field the Barn had for parking, its lit shape looming a few dozen yards up the dirt road, Jenna turned a little grin to her; she couldn’t help herself, it just needed to feel normal somehow. “Remember that one time when we went in there with Joey?” she asked.

Allison smiled — a little wanly, but genuinely, Jenna thought. Allison’s little brother Joe was a world-weary fourteen now, listening to death metal and wearing his own silky-fine brown hair in the greasiest clumps in his face he could manage and dressing in determined uniform black, but at nine he had been a nervous, big-eyed little scarecrow, and had actually yelped when a werewolf-costumed high school kid had gotten in a really good jump and growl. He’d been furious the rest of the night over his cowardice, refusing to speak to anyone. “I think he’s still mad at me,” Allison said, and shut off the car. “Or he would be if I reminded him. Let’s go, it looks like we’re still almost the only ones here.”

They trudged up through the tall grass, into the circle of dim orange light, into the big unconverted doors that threw wide for the season. A pudgy, pretty girl Jenna didn’t recognize — maybe she went to school the next town over — sat crammed into an Elvira dress and long red wig in a folding chair in the narrow entryway. The walls were cheap, hasty fiberboard, sectioning the big barn off into rows of small rooms with as little fuss as possible, and they were peppered with rubber spiders and splashes of red paint around and above her, a sandwich sign with WELCOME TO TERROR hand-lettered unevenly on it propped up on the far side of the makeshift hallway. The girl glanced up at them from her folding chair when they came in, looking surprised. She looked to be playing a solitaire game on the empty chair beside her, with some sort of tarot deck.

“Hi,” she said. “You’re pretty early.”

Jenna blinked at her for a second. “…What, were you expecting us?” She tried to make it into a joke near the end — wooo, spooky! — but it fell oddly flat and matter-of-fact between them. The girl looked unfazed anyway, folding her remaining cards in her lap.

“No, you’re just early.” She gestured vaguely at the hall behind her. “It’s five bucks each for a tour, or two each if you just go on your own.”

“We’ll just walk through,” Allison said, before Jenna could contribute anything else. She was smiling, but a little too tightly. The girl nodded, getting up at last to dig out a battered old green cashbox.

“Two each.” She paused, her hand on the latch. “You sure you don’t want to come back later?”

Jenna glanced at Allison. “We’re fine,” Allison said.

They paid two dollars each, and headed down the hallway. “So where do you want to go?” Jenna said, when she thought the girl was out of earshot; it was hard to be sure, though, she’d been vaguely aware for some time of Red Elvira leaning around in her chair after them, watching them go with an unabashedly wide-mouthed stare, and it had left her too unsettled to play good-times very convincingly anymore. Allison glanced around them for a moment, roving a critical eye around the long, dark hall. The dimly red-lit breaks along its disappearing wall where rooms opened out, the nonsense symbols drawn in fake blood on the partition walls, the dusty floor with its occasional legacy of musty old hay.

“There’s a loft in here somewhere,” she said in a murmur, her eyes still fixed off in the distance. “Or a second floor, even. I need to find it.”

And Jenna opened her mouth with a dozen questions in it; but closed it again almost as quick.

—

They only glanced into the rooms along the left, since they obviously didn’t go anywhere from there. The first one had stage lights covered in red plastic wrap along the baseboards, giving it a pretty decently creepy bloody underlight; the main attraction was a lot less satisfying, though. Most of the room was empty except for absurdly large splashes of fake blood, and in the far corner was a ring of black-robed figures huddled around another form of which only a pare of bare, bloodstained female legs could be seen sticking out between them. Allison was pretty sure only the owner of the legs was being played by a real person: they looked pretty real even in the dim light, and kicked and wiggled from time to time, and there was the occasional faint moan or wavering scream that didn’t sound recorded, but the black robes were all motionless except for the legs’ occasionally fluttering them. There was another tape going in this room, a groaning, ceremonial hum under the main bargain-basement soundtrack piped in over all the speakers. Jenna, who might know better than most people around here, snickered under her breath and muttered to Allison that it actually sounded like Tibetan throat-singing. “Classy, whitey,” she added low, and Allison snerked back in spite of herself.

The second room was starker, and better-done; the red light here showed a red-splattered dummy in farmer’s coveralls hung by a noose from an out-of-place beam across the tops of the walls, with a row of rubber Halloween-shop severed heads in a tumble under his feet, also liberally bloodied. The dim light made it all just a little too believable. Wrinkling her nose a little, Allison wondered how much had gotten spent on red paint and corn syrup this year, and moved on.

She squinted down the hall as they went, trying to keep an eye out for stairs, or a ladder — anything to suggest a second level. She wanted to find some evidence, or better yet no evidence, but it could only really be no evidence if it were in the right place. The stars were beautiful, Lily had written, and she ought to know; Lily had always been the most beautiful thing, the most pricelessly beautiful thing. But there was no way up just yet, just more doorways with half-light spilling through them, gateways to feverish teenagers’ imaginings of the world’s gory worst.

Nobody, in costume or otherwise, jumped out at them, and Allison found herself grateful; her nerves were a little too raw tonight for that sort of thing, charmingly unscary haunted house or no. As a matter of fact, honestly, apart from the careful tableaux inside the rooms they passed, the place did seem weirdly empty. It was only about seven-thirty, maybe they actually were too early for the best of the show. Not that it really mattered to her. She wasn’t here for the show, or not the one these well-meaning kids were putting on, anyway. Once or twice she thought she heard voices in low conversation, down at the far end of the hall where they’d left the girl in the low-cut costume, but when she looked back to see if she could see someone else there — maybe another volunteer, maybe another tour group — she found she couldn’t pick anything out at even that short distance. Something about the darkness of the hallway, the interrupting light, confused space and vision in here. It was like being deep in a tunnel, and somehow your eyes felt like they couldn’t ever quite adjust.

Still, she felt so normal about things past the third room (a pretty good job of putting bloody handprints all over the walls, but the organ jars were tacky and plasticky) and the fourth room (terrible papier-mache cemetery scene, terrible rubber hand sticking out of the dragged-in dirt) that she didn’t even think about feeling normal about things at all. Until, that was, she looked into the fifth room — and all the breath fell out of her chest as if slapped. As if she’d fallen a long way and flattened her lungs on the ground.

The fifth room was Lily. It was Lily, as she’d died.

The fifth room had been crudely mocked-up to look like Lily Packard’s bedroom, clearly a rush job in the details but still gut-twisting in general. The door was in the wrong place relative to the rest of things, and there was no closet, of course, but someone had rigged up the shelves of stuffed animals, the low bookshelves, a cheaper version of the dresser pushed against one wall. There was no wallpaper, but the walls had been painted the right shade of cream, an approximation of the rug spread out over the floor; there was even a black-and-white photograph over the bed that looked oddly identical to Lily’s. The bedspread wasn’t quite the right weave or color, but it was close enough. And the body on the bed — that was unmistakable. It didn’t just look like Lily; even Allison, who knew every corner of Lily’s face better than her own, even she would have sworn if she didn’t know better it was Lily. Halo of white-blonde curls mussed around her head, pale blue eyes staring glassily at the ceiling. Wrists cut in neat gapping T-shapes, trailing rivers of dried blood that had fallen in fans under her hands.

Behind her, Allison could just barely hear Jenna stuttering to a stop, the faint glottal sound she made in her throat, but she couldn’t do anything or even think about it. She couldn’t do anything but hold onto the flimsy edge of the doorway, holding herself up. Just then it was all she could do to keep from fainting.

Neither of them said anything, or did anything, for a very long time.

“What the fuck?” Jenna said at last — almost breathed — and somehow, with that spoken, Allison found that she could almost hold her weight up again, and move. Maybe, she thought half-crazy, because at least Jenna could see it too. She took a few steps forward into the room, getting less lurching as she went along and learned again to balance against gravity. “Jesus, what the fuck?” Jenna’s shock turning over into anger, too, was a good sound, even at its seeming great distance. Reassuring; galvanizing. “Who did this?”

Allison didn’t say anything. She didn’t have an answer. She came to the fantasy of Lily’s bed on legs that felt wobbly and sprung, like the accordioned limbs of a cardboard puppet she’d made for art class once in elementary school. The fake Lily looked no less real closer up. Allison could see a faint glaze of spit dried at one corner of her slack lips. She reached out with one hand, and then started to shake very hard.

And then somehow Jenna was with her, arms wrapped around her, pulling her away. Jenna was a whole head shorter than her, tiny as a bundle of toothpicks, but it couldn’t have been hard to grab Allison and move her around right now; she might as well have been made of straw.

“You think this is funny?” Jenna said after a minute more — except she was really more yelling it now, her head raised away from Allison and voice raising by degrees as more of it came out. “You think this is a joke? Jesus Christ, fuck you! You’re fucking sick!”

At first Allison thought Jenna was just yelling, yelling out at the house in general, to everyone who could hear her, assuming they’d know where she’d gotten to and what she was talking about — until her eyes and brain finally cleared out a little, leveling out slightly in their lunatic swooping orbit, and she noticed the girl in the black dress from the entryway. She was standing in the entryway, very still; staring in at both of them, her mouth slightly open. Enjoying the show of their own, Allison imagined. When she didn’t answer, Jenna snarled — Allison could actually feel it, through Jenna’s narrow chest. Finally, she let go, and stalked away from Allison, and though Allison’s mouth cracked open a little there was nothing there from which to form a protest to anything, not anything.

“What is wrong with you people? Why would it even — ” Jenna got through, her volume piling up into a shrill drilling scream… and then she stopped, not suddenly, but trailing off as though her volume knob had been turned back down again. She stopped talking and stopped walking, and just froze, one of her arms still uselessly up as though to push the Elvira girl. And straightening, able to find a vague, dim frown drifting on her face, making her eyes focus at last, Allison was finally able to see why:

The girl was fake. A dummy, like the one that had been hanging from the beam in the second room. When you actually looked at her, instead of just noticing her at first glance, she wasn’t even convincing. Her features were a bland, anonymous mannequin’s, painted pale and red with Halloween makeup. Her wig was fixed on her head like she was modeling it; her skin down inside her dress obviously cheap, flesh-toned plastic.

Moving as though underwater, Jenna picked back up her wilting upraised hand again, and still before Allison could even begin to form one of the warning words in her soupy mind, she prodded the girl’s shoulder with its fingertips.

The dummy collapsed in a heap, and all the lights went out.

—

They’re out tonight on Lily’s marching orders, over on the far side of town, in the windy parking lot of a plastic-flapped no-name shopping center that’s never been finished and might never come to be. Lily seemed different today when she made the plans, even more different tonight when she came out to Allison’s car: fresh and glowing, after all these months of her strange vague distance, not happy exactly but more like keyed up, excited. Like an electrical current run all under her skin, making its white stand out whiter, her lips’ red redder, her eyes bright and sharp and flat as tin can lids. Allison doesn’t think she likes the change in her, but at least it’s a change. She says where they have to go, says “It’ll be fun, Allie,” and Allison drives her, not because she believes that but because she won’t let Lily go alone if she can help it.

In the parking lot they meet up with a carful of men. Boys, Allison thinks at first, about their age, but as they get closer and she’s introduced (and forgets all of their names almost at once) she starts to think she’s wrong — especially about the one Lily goes to, smiling with downturned eyes into a brief peck of a kiss and then winding her arm into his. It’s nothing in his face or even that she doesn’t know any of them from around town, but there’s something else about him, about all of them, that suggests age, adulthood. He’s dressed with excruciating nattiness, that might be part of it, a button-down shirt tucked spotlessly into dark pants and shiny dark shoes, not sneakers; he has dark hair smoothed back from a strong, clear, handsome brow, and a smile above which his eyes sit sewn on like two shiny brass buttons. He doesn’t look at Allison so much as through her. What was his name? John, or maybe Joe, like her brother? But wouldn’t she remember then? The others are similar, if not the same. One of them wears a windbreaker, and another is slightly fat. But all of their eyes look the same.

John-or-Jack-or-Joe looks across all of them, Lily hanging from his arm. He claps his hands briskly together. “Okay!” he says, quick and cheerful as a dog’s bark. He has an adult’s voice too, pleasant and strong and uncracking. “Okay, okay.” He looks across them again, and they look back, expectantly, waiting. He pauses. “Okay,” he says, one more time. Lily glances at Allison, quickly, her eyes darting over as though afraid of being caught before returning to him. Allison is almost sure she sees that.

“Let’s go to Arby’s!” says one of the skinny guys, triumphant as a wolf, and they all laugh as though this were some kind of joke. “Get some curly fries! What do you say, ah, what do you say?” The heavyset one smiles, a little truculently. Allison looks among them like they were rats down cellar and wishes she could ask Lily who they are.

They go, piling all into the one car. The not-Joe guy sits up front, another one driving, and Lily sits matter-of-factly in his lap; Allison ends up crushed against the door in the backseat, trying not to touch the nearest of the two in the middle, clinging to the inside handle whenever the car turns. From time to time, though she can’t see anything in the crowded dark, she can hear wet mouth sounds from the two of them in front of her. Once inside, they all stand in the brilliant fast food light, Allison trying to keep a polite smile plastered on her face as they crow to each other around her. She’s watching Lily with her date up at the cash register. He cinches an arm around her waist and although Lily leans into it, her shoulders seem to hike up, like his touch has made her twitchy inside her skin. She can’t hear what they’re saying.

Watching them, Allison thinks: They all sound like dogs in the moonlight. And even though they’re all as squeaky-clean-cut as they can be, she’s more frightened for Lily suddenly than she can possibly explain. Not even for herself; she’s got no stake in this, no place in this. That much couldn’t be clearer.

They go back out to the parking lot, loaded with milkshakes and grins and fries. Allison has a soda, but she no more wants it than she does any of this. She lets it go warm in her hand as she stands with the circle of boys (of men), next to her car in all the empty space, and watches Lily and the J-something guy go off to the car they all came in. “Be back in a minute,” Lily said before they went, laughing, her hand still in his like a caught thing in a trap. There’s something so wrong in her eyes. Her laugh is almost mean.

The two of them get into the car and only sit there; she can see nothing but the backs of their heads. The men talk, to each other mostly, although one of them seems to direct something to her from time to time and gives her his animal’s grin, and she smiles back without saying a thing or meaning it. Most of it she can’t even make any sense of, sounds like they’re planning on making a trip somewhere in the near future, somewhere a long drive up north and west. Arguing about who will drive, where to stay (“My mother’s in Seattle,” one of them volunteers; “your mother’s a whore!” another one cries in rejoinder, and they all laugh), what to do. She’s watching J-name and Lily, that’s all. It looks like they’re arguing about something, first he said, then she said. Lily’s mouth open wide, her brow drawn down, raising her voice about something, and then her head turning away to only streetlight-haloed hair. She throws up her hands at one point, between them, and he reaches, and Allison starts as though to step forward in the sudden surety that he will slap her — but he doesn’t, only seizes one of his hands and pulls it to his chest. Whatever passion had seized Lily, it seems to leave her then. She looks away, so that Allison can’t see her face.

It’s cold, and the guy with the windbreaker offers it to her when she shivers as the wind goes knifing by, tossing her hair around her head. She declines. The guy is doing something with Lily’s hand inside the car — maybe drawing on it? She can’t see, and can’t think why he would. And she looks later, when they’re leaving this horror show and getting ready to go home, but by then one way or another Lily’s hand is blank. Lily is turned entirely away from him, shaking like she’s crying or laughing. He finishes, maybe, or maybe just stops, and touches her hair. He kisses her, and she turns back into it like a sleepwalker. They slide down in the seat. Allison looks away.

Eventually she leaves the rest of them, to go over and just stand next to her own car, her keys out in her hand.

Who are you, Lily? Where did you go? What did it make you into?

She throws up out of her car door on Monday morning because the first feeling, the first sneaking thief lock-picking its way into her mind on the news of Lily’s death, was a species of relief.

And when Lily comes to her that night, whatever they came out to do accomplished, her eyes are a big trembly apology that can’t erase the memory of that brightness. In Allison’s hand her own is impossibly cold, all statue stone. The charge has gone out of her; she looks so tired it seems to weep out of her skin like light out of a soft white bulb. But when she says, “Let’s hit the road,” it’s still electric, haunted with the ghost of that shocking meanness — and all her new friends laugh like the dogs they are, and for no reason Allison knows.

—

(from Lily Packard’s journal, near the back)

—

It was hard to even imagine, but after the dark crashed down it was like Jenna lost track of time. She felt vaguely as though she had fumbled out for a while, trying to grab Allison’s hand, but not able to find it in the pitch-blackness of her shocked eyes; and eventually she’d stopped, too afraid she’d get confused and fumble the wrong way, and touch the mannequin-girl again by accident. That had been horrible, a kind of horrible she had no way to describe even inside her head, without a single word. When had that been put there? Was this a part of their stupid show — the dummy and killing the lights? It wasn’t even a little bit funny. And Lily — had that really happened, or had she only imagined it? The longer she was lost the more plausible it seemed that she had. Either way, better hope nobody brought their little kids in here.

She was lost what seemed like a really long time, come to that. The room wasn’t that big, the barn couldn’t have been that big, she should have crashed into walls and found herself with some kind of haste — or the lights should have gotten put back on, whichever one came first — but instead she seemed to stumble on through a vertigo of black for miles, like she was in outer space. She couldn’t have even said how long it was. Once she’d gotten a little of her breath and balance back, she did call “Allison?” once, then twice; but there was no answer, and after that she stopped pretty quick, and that had been her only remote marker of time passing. After that she just wandered.

Finally she actually fell down, she had so little sense of herself or her balance, and it was then on the floor that the shattered logic of the world seemed to come back together a little again. For one thing, she found, as she sat catching her breath on the barn’s dusty bottom, that now that she was down there, she could see light. It was very faint and down low, creeping to her across the floorboards as though it had been cast through an opening at some distance; but it was there. Without even thinking she went toward it — actually crawled toward it, at first, before finally swallowing her deep breath and making herself haul up to her feet.

Eventually, she found the doorway it was seeping in through — one of the flimsy ones cut in those fiberboard walls, she could tell by feeling around it, and that gave her a weird feeling of relief. At least she was still here, although it was hard to say to herself where she thought she might have been instead. The light was still faint, not coming from the room beyond but the one beyond that, double-borrowed. The doorway from which it was coming seemed too far away to be on the other side of that narrow little hallway, though, and it made her frown, although she wasn’t sure where else it could be or even where she was. She’d just gotten so goddamned turned around in here, she could be nearly back out of the whole barn by now for all she knew.

She shuffled across the way between this doorway and that; the light itself was pale in the room beyond, blue and flickering, and it left big parts of the floor in shadow so that she was never sure she wasn’t about to step on something. The closer she got, though, the more confident, and the more the pale gloomy shapes of her own hands and feet swam out of the dark, and then —

The next room was bare, except for two things. One was another one of those stage lights propped along the baseboard: this one covered in blue plastic, and with a bad plug, apparently, because it was flickering almost nonstop. Something about the speed and constancy of it made Jenna think of how her eyelid would sometimes get fluttering when she hadn’t gotten enough sleep in two long. And the other thing, standing in the middle of the floor, was a person, whose shape she could only see in silhouette. (Or another dummy, her brain tried to tell her, and she pushed it away hard.) Back turned, facing the flickering light, and its glow gave the uncomfortable impression that the person was jittering, too, twitching all over in place. Jenna almost held her breath, but as her eyes adjusted and she crept along she thought it was a girl; as she got even closer, it might even —

“Allison?” she tried again, and found her voice close to being a croak. The figure jumped, and whirled around, and she had only a second or two more of not being sure before seeing that it was Allison, pale and gaping with relief.

“Oh, thank god — ” Allison rushed her, and Jenna almost toppled with the weight of the hug, trying to catch her. She was warm and shaky in Jenna’s arms, and her hair smelled sweet, almost sugary. “I, I don’t even know how, I got lost — God, Jen, I don’t even know why I brought us here. What’s going on?”

“I don’t know,” Jenna said, and found her voice a little weak; she tried to firm it up. “But I think we should get out of here. Tell somebody. If they’re gonna — play stupid pranks on us, or whatever, we can come back and look for whatever Lily was talking about once we’ve made them cut it out.”

Saying her name had been a bad idea, though, and Jenna knew it almost the second it was out. Allison was still trembling in her arms, and that made her breath catch, too. “Lily,” she said in almost a whisper a moment later, sounding breathless and teary, and Jenna knew she was thinking of that last fucked-up display — the Lily Packard Memorial Room. Christ, was she ever going to make these assholes pay for pulling a stunt like that. She stroked Allison’s hair back in her hand, making a little soothing noise.

“It’s okay. We’re just gonna go, all right?”

Allison nodded, but didn’t let her go, and Jenna guessed that was all right, after all. Allison was a lot taller and had to sort of fold down into her, but Jenna was strong enough to gather her in and keep her up, and stroked her hair like a mother, soothing her. Allison turned her head in at the touch, pressing her face tighter into the side of Jenna’s neck, as though burrowing in there to be safe.

And after only another second or two, Jenna felt her mouth there. Only a light brush on her skin, but hot, and soft, and wet.

She stopped moving; she couldn’t help herself. Her breath wouldn’t even go in and out anymore. Allison’s mouth moved again, this time even more unmistakably a kiss. Maybe even a little lap of her tongue. It was unthinkable, but it was real — she would swear it was real, and if it was real there was no way she could move, no way she could think or do anything even if it cost her her life. And Allison’s hands were moving up her back, moving up to steal slowly into her hair, kissing a slow deliberate line along Jenna’s neck down to the collar of her jacket, and Allison hadn’t even stopped shaking —

And then Jenna found out that she’d been wrong: she could move to save her own life. Maybe only that, but definitely that. Because Allison, now that Jenna’s whole attention had borne down and focused on every line of her body, wasn’t shaking at all.

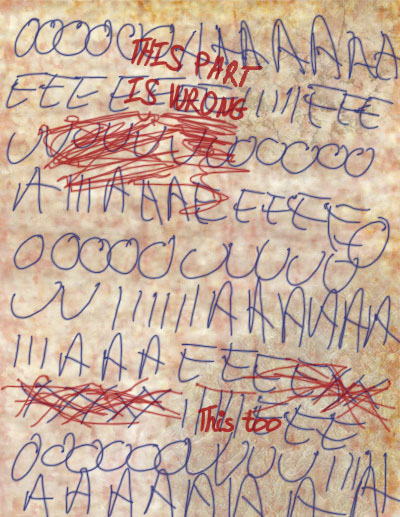

She was jittering. That first impression had been right. It hadn’t been the light at all. Jittering faster than Jenna would have said a person could move, like an old piece of film gone south.

Jenna broke away from her just as she was first feeling Allison’s kissing lips peeling back into an unnaturally wide grin, as they peeled back to her teeth and Jenna could feel them hard on her skin — she scrambled back, leaped back, almost falling on her ass again, her breath all punching out of her at once on the sound of a shaky animal whine she hadn’t even meant to make. When she actually saw the thing she had thought was Allison, furthermore, she had to stuff her hand in her mouth to keep it from coming back, and cranking all the way up. It didn’t even look like her anymore: its features had run together into an anonymous, plastic slump, its fine brown hair gone sticky and started clinging to itself like cotton candy. It was twitching and shuddering on its feet now so hard it looked like an overworked piece of machinery, hands snapping open and closed, arms swinging. Its head lolled onto one side in a boneless, curious flop.

“Aaaaa aaaaa ooooo iiiie uuuuuuuuuuuu ooooooooooo eeeee a,” it said, and then before she’d even known she was moving, before she’d even known she was screaming, Jenna had her gun out from the small of her back and cocked in both her hands and had fired it, again and again, in the wild direction of the thing’s oozing head.

She fired it empty, and then kept squeezing the trigger, still shrieking thinly with some distant corner of her mind she wasn’t even aware of. It fell on empty chambers, over and over, with a series of dry clicks. Eventually she became aware of them, and then slowly the ringing silence that had come in after the gun’s loud crash, making them possible to hear. Somehow, she managed to make herself stop pulling and pulling. A second or two later she realized that she had her eyes squeezed shut, and blinked them open.

The thing was gone. There was nothing in the room but the flickery blue light, and a a scatter of bullet-holes through the fiberboard across from her, through which crazy streams of light from somewhere shone through. Floating dust and particles of wood passed through and got caught in them, like tiny creatures in a tractor beam.

Jenna put the gun down, very slowly, shaking plenty herself now. When she could finally make herself move again, she fumbled in slow motion into her jacket pocket, for the extra rounds she packed along just in case now — like her father, keeping things separate. She reloaded the gun as though she were underwater, taking several tries to get each one into its chamber, and barely remembered to check the hammer before putting it back under her clothes.

It wasn’t, she was able to think faintly, as though shouting it to herself a long distance down a well, so much what had happened, or the monster itself. It was that she had fired her gun — fired it empty — into a thing that had, at least for a moment, looked like Allison.

But the holes said there still had to be light out there somewhere, and where there was light, there was the possibility of escape. And when her wobbly knees would support her again, she got moving toward it.

—

Allison wasn’t sure how she had gotten separated from Jenna in the dark, or why they hadn’t just been able to find each other by calling, and in the end she didn’t think too much strange of it. Possibly they had just wandered apart from each other, gotten separated by space or walls or fear. She found herself out in the hallway again, she thought, when she was finally able to take her bearings — the vague sense of dark openings to either side, with a little light coming in from the doors too, from the floodlights outside. Just a trickle, but enough to get the sense of being back in that long space. When she tried to find the room she’d just been in, though, and Jenna, she found that somehow her disorientation had carried her from it. She couldn’t find anything, or see it even if she had. Well, it didn’t matter. The lights had to come back eventually.

She just went down the hallway for now, pushing the way she should have been all along; she could meet up with Jenna later, when they both had their bearings back. Something about the sudden dark had slapped sense back into her, forced that image of Lily’s bled-out body (and it hadn’t been her of course, just an act, just some other trick) to assume some sensible size and shape inside her mind again. She could wrap herself around it now, digest it, and have it be gone. She just needed what she’d come here for.

She was making her way with such determination, and the hallway so dark, that she actually fell over it. Her shin struck hard against a sudden sharp corner, only barely cushioned by her jeans, and she bit her lip on a cry of surprise and pain and lost her balance, tumbling forward with her hands stuck out blind to catch herself. They did, and much sooner than expected — with her not much more than leaning forward, not even fallen further than a sort of half-bow. They caught with a hollow thunk on wood.

Allison caught her breath for a second, and then a moment’s feeling around, and squinting against the dark, found her the shape of the thing she was holding — its edges and dimensions. And the one below it. And the one above.

She had fallen across a steep flight of rickety wooden stairs.

A loft, or a second floor, she had told Jenna; the ceiling was impossibly low in the rooms down here, no higher than the height of half the barn. There had to be another place, a higher place, even if it was only an old rotting hayloft or a ramshackle lookout point where somebody could sit and let the rest of the Fright Barn kids know more suckers were on their way. Someplace a person could see the stars, and be near them, like Lily had described in loops of blue pen when she had still been alive.

Well, here she was. Stairs meant up. And after no hesitation at all, Allison went up them.

—

But they don’t go home then, not yet.

All of them pile back into cars, segregated by sex once again, and drive. Allison follows the men’s anonymous dark car through the nearly empty streets, and Lily doesn’t talk to her, so she doesn’t say anything either. They sit in a staring-ahead silence as heavy as clay.

The car leads them to a building out past the city limits, nearly out in farmland: a low squat square thing painted some dark color — maybe black, maybe red. It looks less like a house than some inbred spawn of a pool hall, a high school gym, and a state welcome center, but inside the front door it’s a funny kind of domestic. There’s an entryway and a long hallway with a black-and-white-checked linoleum floor, at the end of which Allison can vaguely see a doorway disappearing into what looks like a living room on one side, maybe a kitchen on the other. It’s a long hallway, though, painted an off-putting brick color. And every door along its length is closed.

“Wait for me,” Lily says to Allison, and Allison can see she isn’t feeling mean or funny or anything like that anymore, whatever that was before. Her face is drawn tight, colorless, and she keeps her voice low. Her hands wind into both Allison’s between them, and Allison can see a couple of the men still standing off to the side, grinning over them. Some have already disappeared. “Stay out here. Don’t go anywhere.”

“She can if she wants to,” says J-name. He’s standing to the side with his hands in his pockets and his grin looks much too white and toothy. “It’s a free country.”

Lily looks at him — hard, Allison thinks, and long, although he’s on the wrong side of her and she can’t see exactly what Lily’s expression is. But then she turns back to Allison and looks just the same. “Stay out here,” she repeats. “Don’t go anywhere.”

“I will. I mean, I won’t.”

J-name, No-name, he takes Lily’s hand. Taking one of them right out of both Allison’s. Lily doesn’t look at him; her eyes are cast down.

They disappear into one of the rooms along the hall. Allison sits down. There are two plushy black leather chairs in the entryway, next to a little end table with a small statue on it, and she sits in one. The other two guys stand there in the entrance grinning at her for several minutes, but when she doesn’t respond to them eventually they, too, wander down the hallway and out of sight.

Allison waits. There’s a clock on the wall opposite her, plain and marked only in hatchmarks. It ticks off the seconds in a muttery undertone, and she waits.

It’s been only something like ten minutes when there’s a faint thump noise, down at the very bottom of her hearing. She isn’t even sure she heard it, and her head jerks up, a frown drawing over her face. She listens for it to come again, but there’s nothing. Just the ticking clock and the occasional wind blowing up outside. Far down at the end of the hallway — or did it come from inside one of the closed rooms? — someone laughs, someone with a deep male voice. There’s another thumping sound a little later on, but this one doesn’t sound dangerous or strange; it sounds architectural, a drawer closing or a chair being pulled across a floor.

About half an hour later, so muffled and wavery again that it almost doesn’t register in her hearing, a woman screams.

That, though, she’s almost sure she did hear. She scrambles to her feet, her breath caught, wide-eyed and staring. She stares down the hallway, but of course there’s nothing to see — just yards and yards of closed doors. There’s nothing else. Still —

“Lily?” she asks, and is a little startled by the sound of her own voice over the clock. Long, spun seconds of silence… and then something faint and thick, almost like a moan. Her hands curl in on themselves, squeeze, relax. She listens for a few seconds longer. Nothing.

So she starts down into the hallway, creeping almost, putting down half her foot at a time so she muffles the sound of her footsteps. Making her slow quiet way on that tile floor, toward the door No-name and Lily went into (but was it? Was it actually the second one on the right? Now she can’t seem to remember, it could have been the second one on the left or the third one down after this, and what if she goes bursting into the wrong one; what’ll she find there?), stretching out her hand inch by inch toward the doorknob —

Her fingertips have just lit on it when a hand closes around her wrist, and she almost screams herself. In the end, it gets no further than a high, shivery sound, nearly dead before it leaves her throat.

“You can’t go in there,” says one of the men from earlier — the one with the windbreaker. He has a slightly more human expression on his face now than she’s seen there for the rest of the evening beforehand — a little tenser, a little more open, maybe even concerned. Maybe even afraid. “Sorry.”

“What the hell is going on here?” she snaps at him, trying to wrench her hand away. And failing — he has it good and tight. She hadn’t quite meant to snap, but he just scared her so badly. “What’s he doing to her?”

“You can’t go in there,” is all he says, again. His eyes look a little like he’s trying to convey something to her with them, but if so, she can’t read what it is.

“She could go in another room, though,” another one says, from down at the end of the hallway, where the doorway is. The one holding her didn’t come from there. Where did he come from? Another room, or does she only think that because the other one just mentioned it? He’s grinning, anyway, nastily. There’s nothing more human about his expression. “If she wants to. We could go in there and have a parrrrrrrrrrty.” He draws out the R very long, and soft, like he’s pretending to be from Boston or something. Allison tries to shake her hand free of the guy holding her again, but still has no luck, and when she glances at him he’s just looking down at the other guy dumbly and seriously, as though a very important theorem has come up in conversation and he wants to give it some thought.

“Lily told me to stay,” she says, and is dismayed to find her voice sounds thin — almost little-girl-ish. Mother, may I? Yes, you may.

“Yeah, but you didn’t,” the guy says, and now he’s coming up the hallway, at a slow, relaxed pace, like he’s window-shopping his way up the hallway. She has a crazy second’s wondering if there are other people behind all of these doors, and if there are if they’re getting annoyed with all the chatter. What they’re doing in what she’s suddenly certain is darkness, each room, every room. “You didn’t. You didn’t do that at all. So I think maybe you don’t listen. I think maybe you want to — “

“No!“

Muffled at first — crazily muffled, far too much so, too much to make sense at such a short distance. And then a door busts open — it’s the first one on the right, the first one, how could she have forgotten that — and then there’s Lily, eyes blazing and a shocking mess. “You let her go!” Lily shouts, nearly screaming, and hammers the heel of her hand at the guy who’s holding Allison. He drops her hand at once, and again it’s almost as though he’s a little afraid. Lily’s hair is adrift and tangled on itself, her face as puffy and ruined as though she’s been crying all the time she’s been gone; there’s a rim of dried blood, Allison can barely credit that she’s seeing through her dreaming horror, around her nostril, a little skim down below where there was more. Her too-old, grownup dress is torn at one shoulder, showing half her bra. “You get the hell off of her right now, I’m warning you! I’m warning all of you! I said no and you agreed! You agreed! You agreed!“

The two guys have fallen back by now, with uneasy expressions of mingled alarm, amusement, and fear, but Allison soon sees this is not because of Lily but because No-name has come out of the room behind her, and is looking around at them both. He doesn’t look angry, but only faintly disgusted, as though an important play had been fumbled in a football game he was watching on TV.

“Take a hike,” he says, calmly, without raising his voice, and puts his hands firmly on Lily’s waist. Lily stops struggling and moving to attack the guy with the windbreaker at once, but it’s no good really; she just goes limp in his hands like a doll, quivering, her head dropped so far down even her shortish hair covers her face. For his part, the guy with the windbreaker takes a hike so fast it’s like he made himself disappear; he tears back down the hallway and out the front door. The other guy disappears through the far doorway, and No-name turns Lily in his hands, to face him. He tilts up her head a little with a hand under her chin, runs his finger under her wet eyes with a look of serious tenderness, like an adult tending a toddler’s scraped knee — and then suddenly brings his finger, wet with her tears, to his mouth and licks it clean. Allison’s stomach flips and crushes itself, so fast and violently she has to whip her head away and dig the ball of her thumb into her other inner wrist, staring water-eyed at nothing, to keep from throwing up.

When she can finally look again, not only is it over, they’ve both disappeared again. The door to the room, no doubt where they are, stands open, but she has no urge to look inside. None at all.

A few minutes later, Lily comes back out of the doorway, moving slower and looking calmer and more herself, although still red-eyed. Her face and hair are damp, and the blood is gone from around her nose; her dress has been healed with a big safety pin. You could believe she’d just had some sort of accident. She doesn’t look at Allison, though, and the guy follows her seconds after, his hands back in the pockets of his pants, smiling. He looks so vibrantly, artificially normal he looks made of plastic.

“Better take this girl home,” he says to Allie, and winks at her, big and sitcommy. “I think she’s a little worn out.”

“Go to hell,” Allison says. She doesn’t really plan it; it just comes out that way. Lily flinches at the words as though they were a gunshot. And for a second she’s suddenly sure, not just thinking but sure, that neither of them will leave here tonight. Or ever again.

But nothing happens. And before nothing else can happen, she’s grabbed Lily’s hand in hers and gone striding down the hallway, not quite fleeing, the guy staring and smiling after them like a poster of himself.

—

(from Lily Packard’s journal, the last two pages)

—

Almost as soon as there light to do it by, Jenna started seeing them.

The doorway out of the room where the — whatever had gotten to her didn’t lead back out to the central hall. Instead it led into another room, of about the same dimensions, just as thin-partitioned and just as bare. When she tried to picture what way that meant she was going, or how she had even gotten to a part of the barn where things worked like that, or what way the hallway should be from here, her feeling of vertigo was so total and spinning that she had to stop for a second with her hand up and groping for the wall, fighting down nausea. The room didn’t have a window to the dark outside, which could have meant it wasn’t on the outside wall, or could have meant nothing. Neither had the last one, come to think of it.

But it was lighter in here, the blue flickery light behind her crashing and warring against a plainer, brighter white light from up ahead. There was another doorway there, spilling glow across the dusty old boards of the floor, and she crossed most of the way to it without realizing she’d taken her gun back out and was holding it in her hands. She didn’t know which was worse — that, or the fact that she’d actually started thinking of it as her gun — and it didn’t seem like the greatest idea maybe, but she couldn’t seem to help it.

Through that doorway was, surprise, another identical room. She had the half-formed idea that this was some sort of staging area at the back of the barn, where the kids running it hid out normally while waiting for people to show up to jump out at, or where they kept things between haunted houses, but somehow she didn’t quite believe it. The further she came, the less sure she was that any of this had anything at all to do with the show as she understood it. The room was lit by a single bare bulb, dangling from the ceiling, and it was blank as the highway here had been. She made her way in cautiously, stepping quiet for no good reason she even knew.

At first, she didn’t even notice. They didn’t come like a part of the world would come: found in a corner as she turned her head, say, or entering her space through a doorway or a window. They unfolded themselves out of things, out of a nonexistent space inside the whole of where she was — not just the room or the barn but the whole everywhere. She didn’t see them at first because at first all there was of them — there or anywhere — was fingers, and that was easy enough to miss in the dark floor and the odd shadows thrown by the overhead bulb.

Then a flicker of motion caught the corner of her eye, and she whipped her head to the side — and at first, still didn’t see anything. Her heart had thrummed back up to full speed, but even while she was trying to tell herself it had just been one of those false positives, or at most a spider or something, her eyes fixed and she found the motion in among the whorls and dust of the floor. At first she thought splinters of one of the floorboards had been popped loose and something was pushing up on them, and that was bad enough — just something long and spindly and scuffling, shoving up out of the cracks in the floor that were really too narrow for anything to come up out of. Her breath dried up, her feet fumbling to a stop in a tangle with one another, and as though it had been a spider, all she could do was stand and watch, her face numb and locked down into a hunter’s adrenal blank.

Then the long splinters flexed out and up before bending again, out into the room, and she could see they didn’t look sharp at all, not like wood at all. They looked —

They found purchase: not in the floor, but in everything. In the very substance of things. They clenched. And pulled, and their greyness whitened with pulling; reality seemed to ripple, to pinch and buckle slightly, and then there were whole hands appearing at their roots, palms and spindly many-jointed thumbs, knuckly wrists like thick knobs of chalk, emerging from nowhere into somewhere.

Jenna staggered back, captured breath whining in her throat, but that only gave her a wider view and let her see that wasn’t the only place where it was happening. There were others — it looked like dozens of others, actually, sets of hands emerging in jittery, out-of-phase waves from what seemed suddenly like every surface of the room. She whirled around, looking behind her, then back around, unable to take her eyes off any of them. Her hands were clamped on her gun so tightly it hurt, she would find later it had dug bruises into the meat of her palms.

They were just unsynchronized enough to keep it from being funny, or even beautiful, but they all moved at roughly the same time. The hands spread apart, and although there was no real sound there was still the sense of the sound of something being torn. Shredded apart, and crying out with it, like fabric with a hole yanked through it. For each, one arm flailed out. It was skinny, nearly meatless, its grey skin mottled and shifting and weird, and it looked like it had too many elbows, or maybe not enough. It reached ahead as the other held back, like a swimmer’s arm, and the thing’s head and shoulders followed, humping up out of the floor in a spineless fold. The top of its head pressed on the floor (on the world, Jenna’s mind insisted again) for leverage, and then folded under as it moved forward, doubling back completely into its concave grey chest. The only mercy was its face was hidden; even a glimpse of that had been bad, unbelievably bad.

She couldn’t move. Frozen there, feeling the hugeness of her eyes more than meaning for it to happen. News from somewhere else.

The thing crawled its arms along, paddling the floor, the other one leading now, and more of it lifted out of nothingness. A humpy, waved spine, low-slung wavering skeleton hips. Then one never-ending leg, crabbing up to set its spindled foot on the floor at an equally impossible angle, and then swimming that up over its shoulders as well to execute a tangled head-hurting tumble of a flip and lift out its other. And then it was out. It was there. They were all there, in loose jagged-edged twitching heaps. Some on the floor, and that was one thing, but still more were just lying like that on the walls, and that was much, much worse — and she could just see periphrally, didn’t dare look, that still more were doing it on the ceiling, had pulled themselves out of the ceiling and now lay on it like broken toys on a kid’s bedroom floor —

“Aaaa uuueeeee eeeee o,” the one Jenna was watching said, into its own chest. “O o o eeeei eeeei, aaaaaa”

At first it was the only one. And then all the others answered — and the room was an unutterable cacophany of groaning, jittery mutters, like the thing that had looked like Allison. Jenna staggered back, her lips peeling helplessly away from her teeth, fumbling her fingers around the gun. And all of them, this time all at once, snapped their heads to the side out from under them and toward her.

“AAAAAIIIIAAAA,” the one nearest, at her feet, said in something that lacked only the possibility of emotion to be a jubilant cry. It shivered, and then clambered, putting down its feet and hands in no particular configuration to push itself toward her. Its head was held upside-down, then sideways, as it swam-crawled over itself, sometimes sorting itself out into some sort of linear arrangement only to fall back into a crumple again. Now she could see its face clearly, as little as she had ever wanted to. It had the grim, interested expression and skin-crawling alien grotesquerie of some of the pictures she had seen of things that lived at the bottom of the ocean, hundreds of miles from light. But maybe not like that at all. It was hard, she was aware only at a tremendous distance, to see. The light was flat and unforgiving and it only a few feet away, but it was hard to see it. It was hard to think it. It was hard to let it exist in her mind.

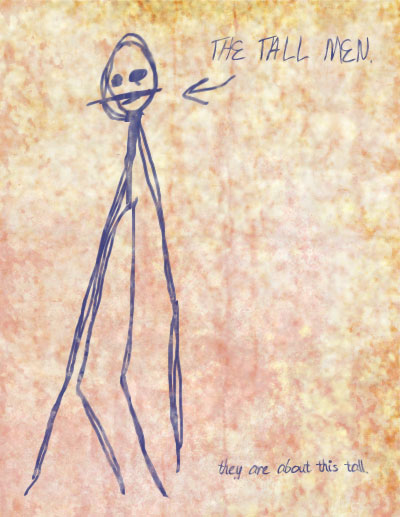

The drawing in the diary had been crude, almost childlike, but she still couldn’t have mistaken the things having seen it. It was them. The Tall Men. Lily’s Tall Men. They were real, and these were them.

Jenna’s thumb scritted like a crazed rat’s feet at the revolver’s hammer, and they crawled out.

—

The stairs were steep, and doubled back on themselves once, leaving Allison in such darkness she had no way of placing herself but still feeling at an incredible height. They weren’t rickety, at least; the wood was heavy and hard and firm underfoot. That was something.

At their top, she emerged through a hole in some ceiling more sensed than seen, into a hay-smelling darkness even dustier than the rooms below had been. It was unthinkably dark up here — not a star to be seen. She felt around for long enough to know that she was in the middle of some broad space, with little to define it, and then decided she shouldn’t run the risk of falling back through that hole and down the stairs. There was a little squeeze flashlight on her car keys with the name and address of her dad’s real estate office on it, and although it didn’t produce much more than a pinhole’s worth of light she brought it out anyway, and squeezed it around. Not much — but she was able to pick out the vague angles of a support beam, some six or seven feet away, and made her way toward it without thinking too much.

And the most unexpected boon of the whole night: there was a switch on the far side of the pillar, as the felt around it, a heavy hard black plastic button, like something industrial. She pressed it, not knowing what to expect — but floodlights came on, without a hesitation, along the far-up ceiling of the loft, lighting its whole interior as bright as day.

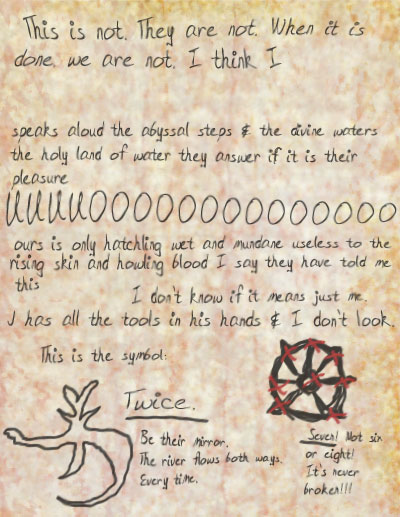

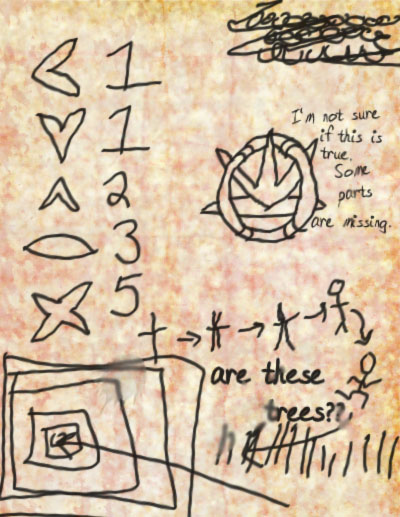

It was a huge, empty, open wooden space, a little smaller than a football field, it seemed to her. Although maybe that was just the way the edges of it seemed to disappear into shadows, beyond even the giant lights’ reach. There were no windows or apparent doors anywhere, although a sprawling, yards-wide white symbol had been chalked on the floor — one Allison thought she recognized from Lily’s journal, actually. She stared at it for long moments before finishing her sweep. Otherwise the only things up here were her, more wood support beams set at occasional intervals, the hole to the stairs she had just clambered up from… and a long wooden table stood in front of a huge, sprawling, apparently free-standing wall of mirrors.